Koesister Mentality: Sweet Spice, Survival, and Sunday Mornings

More Than a Doughnut

The koesister is not just fried dough dipped in syrup. It is a Cape Muslim archive you can taste: slavery and spice-routes folded into flour, patience stitched into the rise, mercy poured as syrup, and community dusted on like coconut. On Sundays in Cape Town, this is how memory is served warm.

From Chains to Sweetness: Where it Comes From

Enslaved and exiled people from Indonesia, Bengal, India, Madagascar and Mozambique brought spice grammars — cardamom, cinnamon, ginger, aniseed — into the Cape. In cramped kitchens they kneaded survival into foodways that became Cape cuisine.

The koesister was one such vessel: a creole of technique and faith, born in constraint, perfected in community.

Koesister vs Koeksister — why the “e” matters

The Cape Malay koesister is a spiced, oval fritter simmered in syrup and rolled in coconut. The Afrikaner koeksister is a plaited, crisp fry dunked into cold syrup. They share a Dutch “koek” root but took divergent paths: one scented with aniseed and Sunday barakah; the other with braids and brittle sweetness.

Grinding the Memory

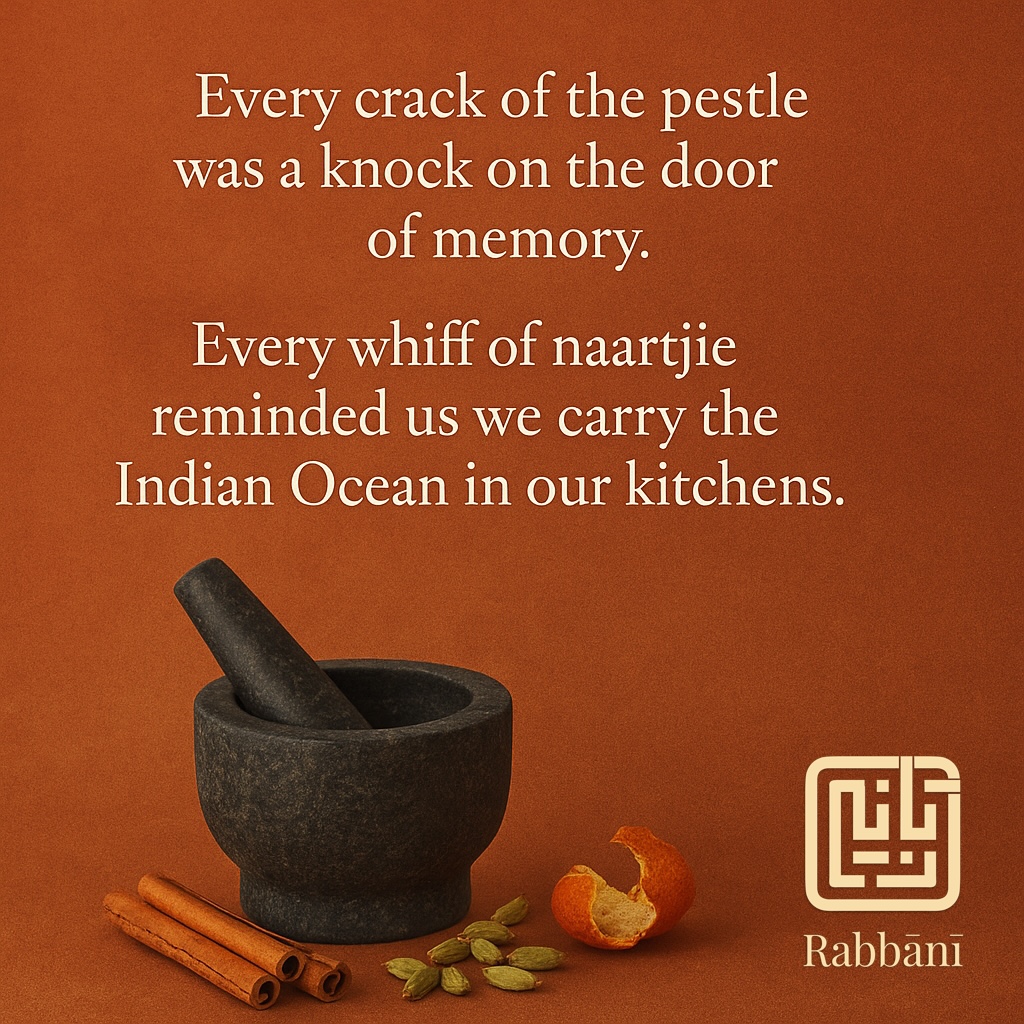

When I was a child, I would sit on my bum on the stoep, mortar and pestle between my legs, grinding cinnamon, cardamom, aniseed, and dried naartjie peel. The air filled with perfume, and I knew without knowing that these were not only flavours — they were history.

Spices that had crossed oceans with enslaved women were now ground by a child’s hands on a Cape Town stoep, ready to become part of Sunday morning koesisters. Every crack of the pestle was a knock on the door of memory, every whiff of naartjie a reminder that we carry the Indian Ocean in our kitchens.

Sundays in Primrose Park

I remember sugaring koesisters outside our front door in Primrose Park. Neighbours would stand in line on Sunday mornings, bowls in hand. My Tietie, Gadija — Dija, may Allah have mercy on her — made a koesister that was simple, fragrant, and always in demand.

She would wrap the dough in blankets to rise, then fry and dip until sticky, coating each with coconut. People didn’t come only for the sweet; they came for what the sweet held: blessing, neighbourliness, and survival in sugared form.

Two Recipes, One Lineage

Tietie Dija’s Koesisters

- 1 kg cake flour

- 2 large eggs

- 1 tsp fine salt

- 2 tsp each cinnamon, cardamom, ginger, aniseed

- 1 pkt yeast

- ½ cup oil

- 1 ½ cups lukewarm water (not more than 2 cups)

Method:

Sift dry ingredients into a large bowl. Add eggs and oil, mixing with both hands until crumbly. Add water and knead into a ball. Cover with a bread packet and wrap in a blanket. Leave to rise for 2–3 hours. Fry, syrup, and serve with coconut.

Salwaa’s Cape Malay Cooking Koesisters

- 1 kg cake flour

- 2 tsp ginger, 3 tsp cinnamon, 1½ tsp cardamom, 4 tsp aniseed

- Optional: dried naartjie rind

- 10 g instant yeast, 1 cup sugar, 2 cups hot water, 2 tbsp butter, ±2 cups milk

- Oil for deep frying

Method:

Melt butter and sugar in hot water, add milk to make 1 litre. Mix with flour, spices, and yeast to form a soft dough. Let rise until doubled. Shape into balls, then oblongs. Fry until golden. Dip into syrup (sugar, water, cardamom, cinnamon), and sprinkle with coconut. Optionally slit and fill with glazed coconut.

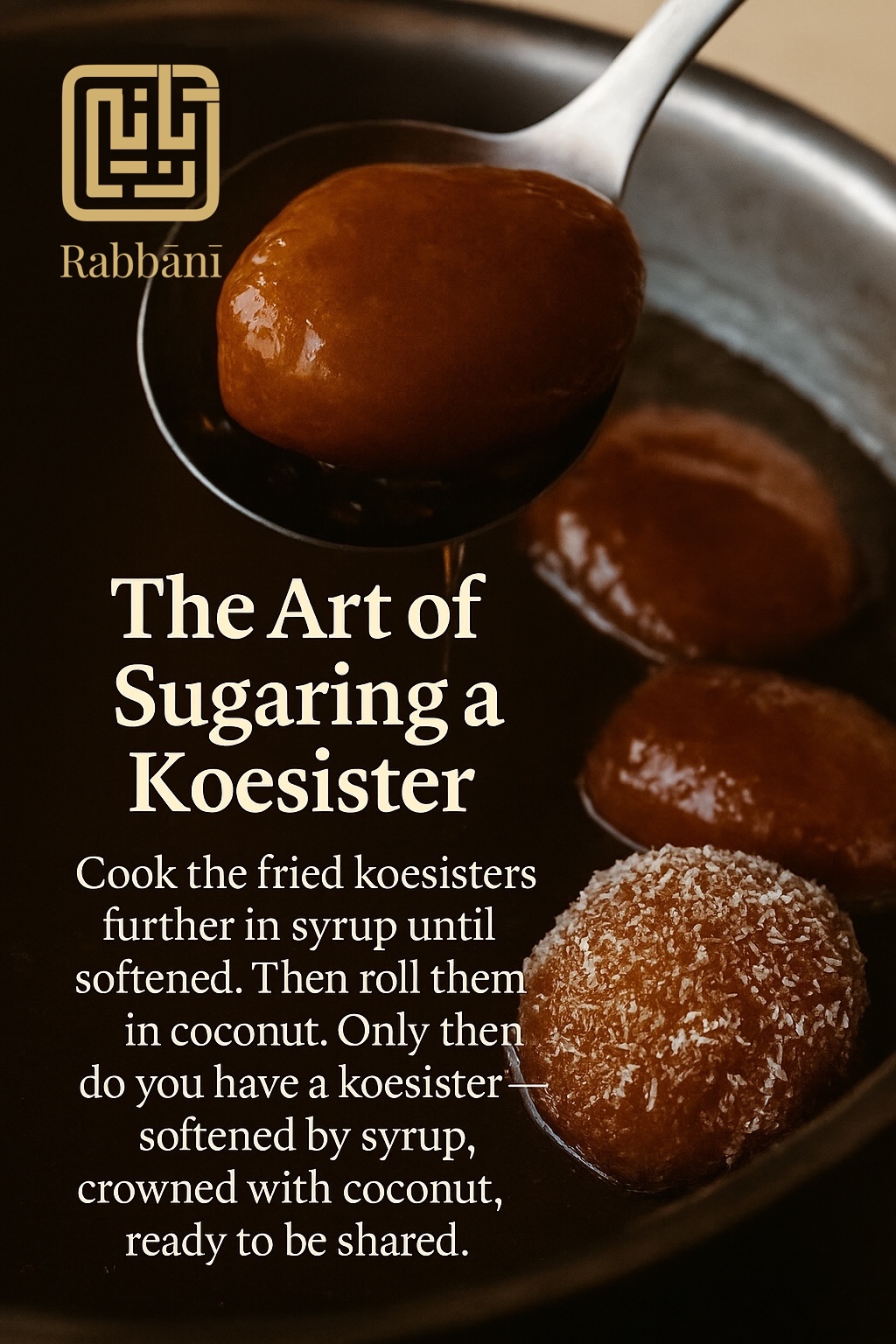

The Art of Sugaring a Koesister

People often miss the essence of the koesister. This is not the crisp, cold-dipped koeksister. Astaghfirullāh, you don’t just fry and dunk.

In a nice biggish pot you cook:

- 1 cup water

- 1 cup sugar

- (Optional, but beloved: cardamom, cinnamon, and even a touch of honey for barakah and shine).

Watch the pot until it starts to get sticky. You test it with a spoon: lift the syrup and see how the drips slow down. That’s the sign.

Now — and this is the secret — you add in the dry fried koesisters to the pot. Stir them gently, let them continue cooking together, prod with your spoon until they soften and drink the syrup. Keep a cup of water ready when it gets too sticky. But use it sparingly. Only then do you take them out, roll them in coconut, and place them in the bowl.

That’s when you have a koesister: softened by syrup, crowned with coconut, ready to be shared.

The Barakat of the Koesister

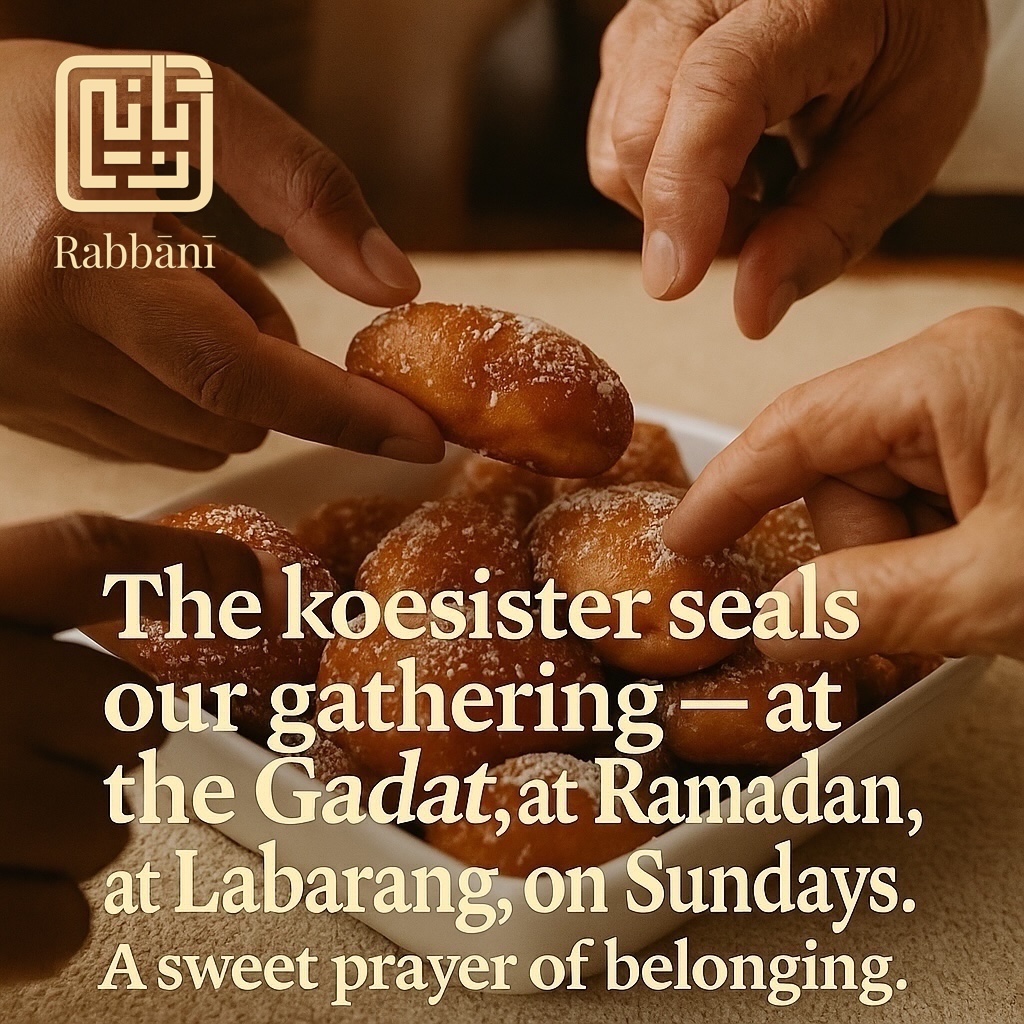

The koesister is not confined to Sundays. It turns up wherever barakah gathers:

- At the Gadat (dhikr circle): trays of koesisters pass between voices chanting the Divine Names, sweetness sealing the remembrance.

- At weddings: slipped into barakat parcels — alongside nuts and sweetmeats — a reminder that joy is for sharing.

- In Ramadan: laid on iftar tables, syrup echoing the mercy of breaking fast.

- At Labarang (Eid): no celebration is complete without sticky fingers and coconut laughter.

- Every Sunday morning: queues outside homes in District Six, Bo-Kaap, Athlone, Primrose Park.

In all these settings, the koesister is a seal of blessing: a sweet amen after prayer, a sugared handshake of belonging.

Symbolism: What the Steps Teach

- The yeast: intention, a spark that lifts everything.

- The rise (under blankets): hidden work, dignity rising even in silence.

- The oil: trial by heat — sabr through fire.

- The syrup: mercy, binding the cracks and soaking to the core.

- The coconut: hospitality, a dusting that says this is for sharing.

- The Sunday bowl: community, where every vessel is filled, no one excluded.

This is why elders said: Life is like a koesister — not so lekker if eaten raw, but sweet when endured, fried, and dipped in mercy.

Koesister Mentality: Sweetness After Struggle

To eat a koesister is to eat history — slavery, spice routes, resilience, survival. To make one is to carry that tradition forward.

Koesister Mentality is more than humour or heritage: it is the ethic of rising, enduring, softening with mercy, and sharing abundance. Sweetness after struggle, but never without memory.

Once, “koesister mentality” meant narrow thinking. But I steal it back, and sugar it differently: for me, koesister mentality is resilience after rising, sweetness after struggle, and barakat in every bite.