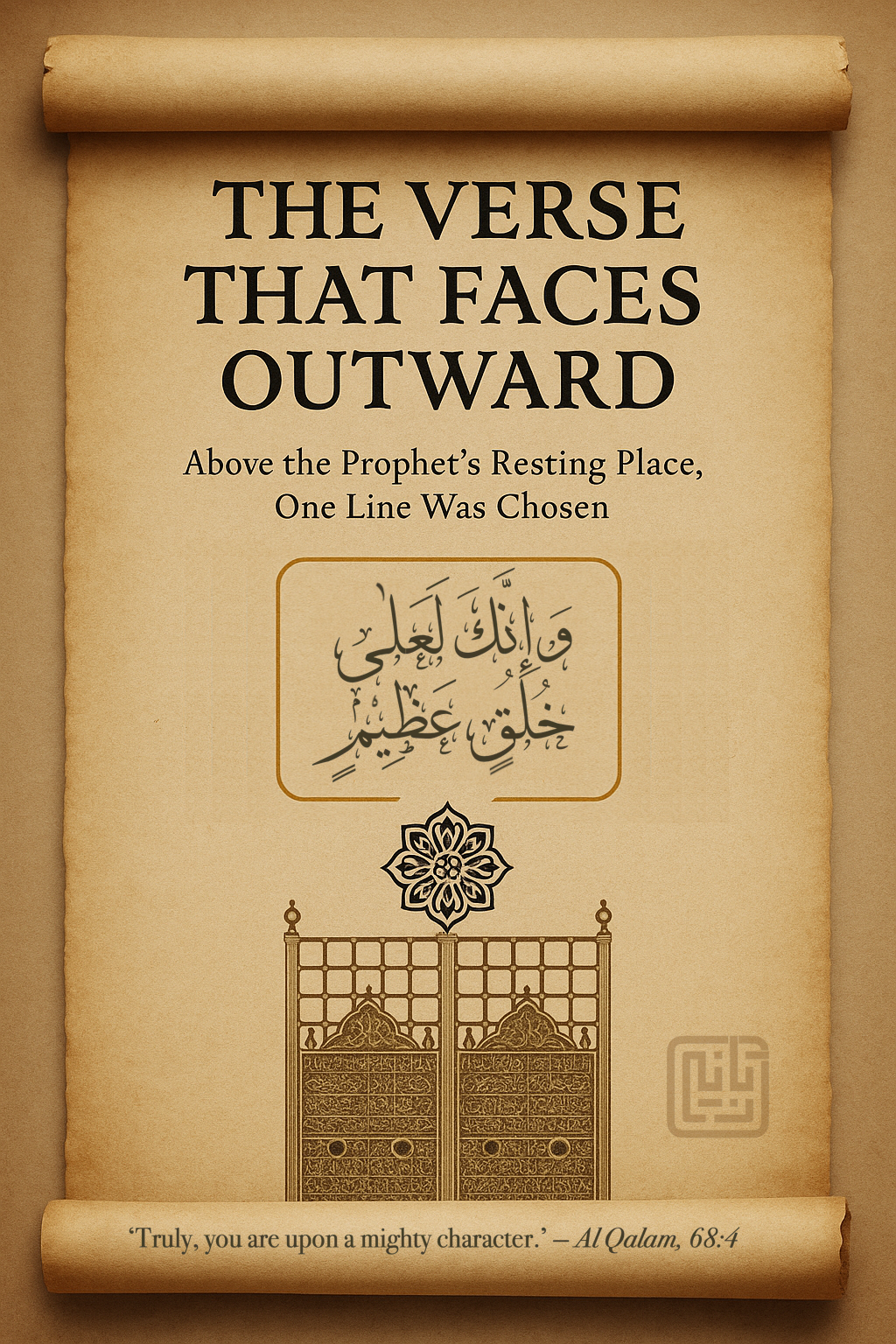

The Verse That Faces Outward

The Hidden Poem Above the Prophet’s Gate

A Knock Upon the Door: A Poem Hidden in Stone

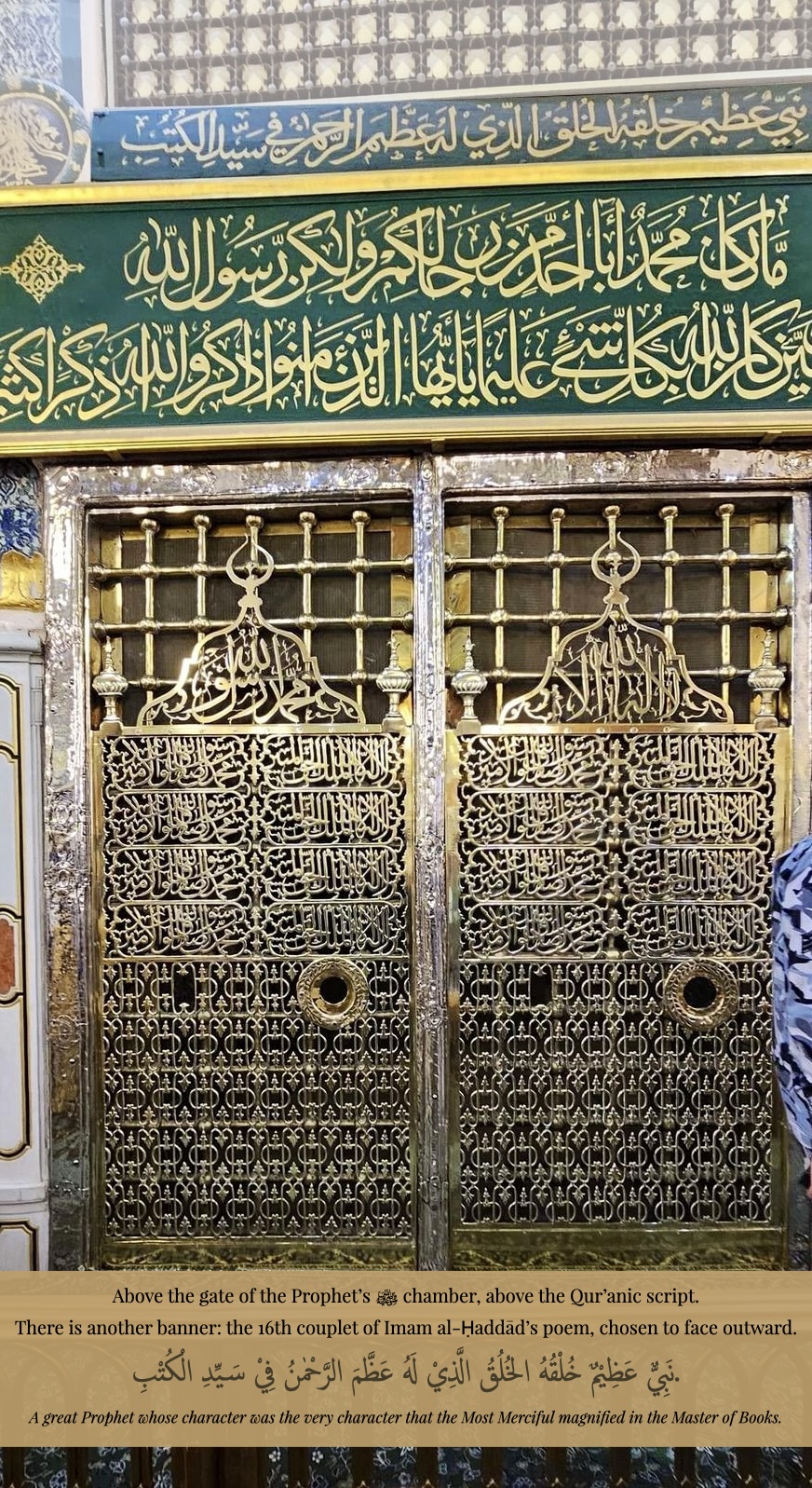

In the sacred precincts of Madinah al-Munawwarah, where pilgrims send peace upon the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him), few notice a quiet miracle. Above the gate to the Rawḍah — where our Prophet rests — is an engraved verse of Arabic poetry, nestled in plain sight. Most eyes pass over it, drawn instead to the Qur’anic verse below. But that upper verse is from a 40-couplet qaṣīda written by Imām ʿAbd Allah ibn ʿAlawī al-Ḥaddād — a saint, scholar, and Sufi of the Bā ʿAlawī lineage of Tarīm. Only one couplet of the poem is visible to the public.

One line.

Facing outward.

Why this line? Who chose it? What does it mean that the rest of the poem lives inside, engraved on the inner walls of the chamber of the Prophet ﷺ? What does it mean to be the line that stands at the threshold?

This blog is a gentle unfolding of those questions.

a single couplet from Imām al-Ḥaddād’s 40-verse ode, chosen to stand above the Qur’anic verse.

Some verses open books. Others open doors. The chosen line stands where praise meets Revelation.

Section 1: The Verse That Faces Outward

نَبِيٌّٜ عَظِيمٌ خُلُقُهُ الخُلُقُ الَّذِي لَهُ عَظَّمَ الرَّحْمَنُ فِي سَيِّدِ الُكُتُبِ

A magnificent Prophet — his noble character,

Exalted by the Most Merciful in the Master of Books.

Imām al-Ḥaddād is drawing from the Qur’anic verse:

“And truly, you are of a most noble character.”

(Surah al-Qalam, 68:4)

In these lines, poetry bends in humility before Revelation. The poem is not in competition with the Qur’an. It is a witness to it. A praise that holds its breath before the Word.

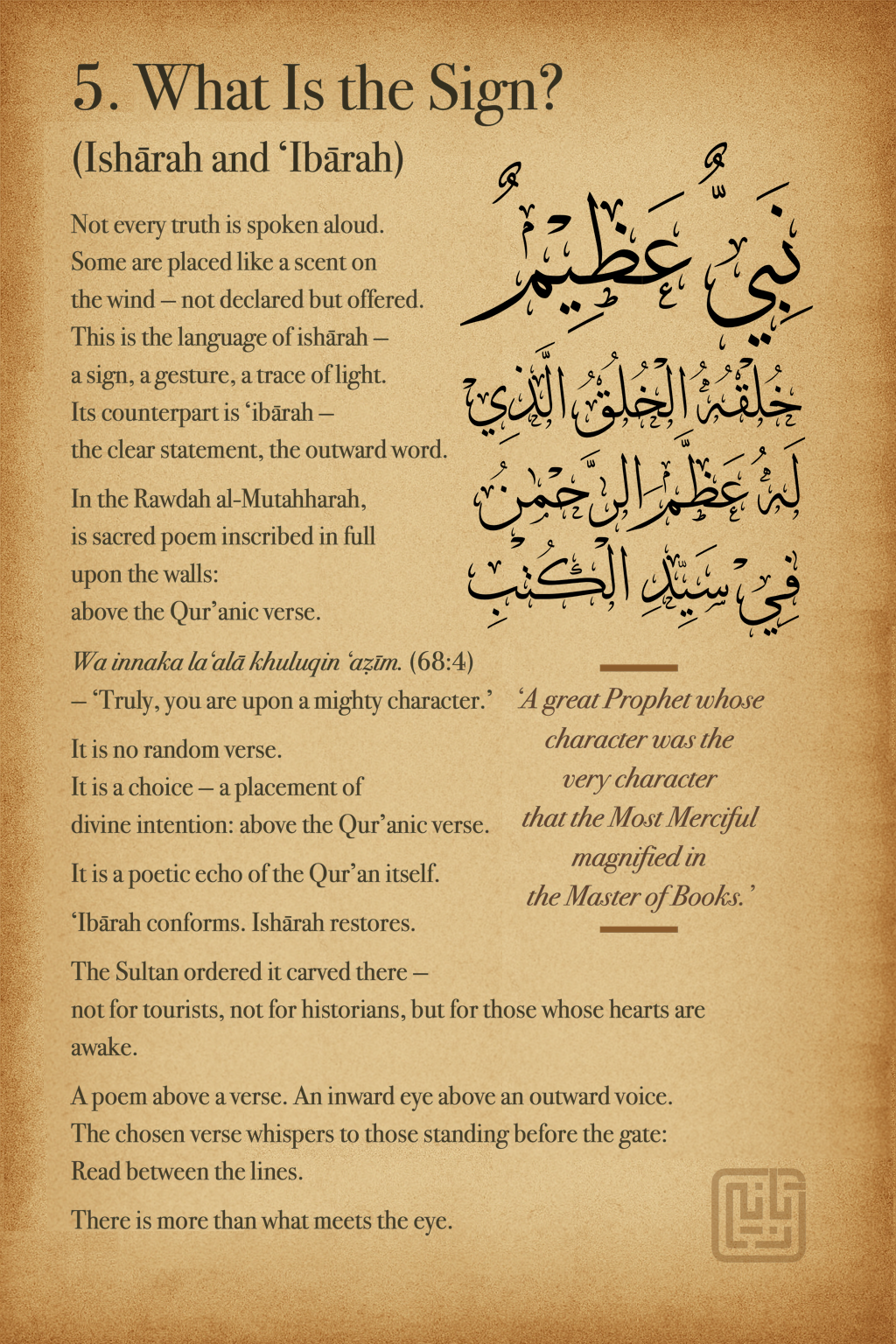

Section 2: Ishārah and ʿIbārah: The Inner and Outer Signs

What is visible above the gate is the ʿibārah — the outward expression. But the choice to place this verse there is also an ishārah — a subtle sign. It whispers: Look closer. Listen deeper. The rest of the poem remains inside the sacred chamber, out of sight, like the hidden knowledge that only the heart can read.

The verse that faces outward becomes a threshold, a knock upon the door. A visitor may stop to read it, but the meaning enters only when the heart listens. As Shaykh Jamiel said: “Most people see the ʿibārah, but few perceive the ishārah.”

And that is the invitation.

Section 3: The Hidden Inheritance

There is a story passed down from the early life of Imām al-Ḥaddād. When he was still an infant, his mother dreamt that she was at the tomb of a great spiritual master. In the dream, the master emerged from his grave, took the baby to his breast, and gently placed his tongue into the baby’s mouth.

In the language of sacred dreams, this is no ordinary image. It means that the child inherited the master’s knowledge — not through books or teachers, but through direct spiritual transmission. Through the tongue. Through barakah.

When we recite the Ratib al-Ḥaddād, we are inheriting from that lineage. When we stand before the gate and read the outward verse, we are brushing our lips against the memory of that transmission.

Section 4: The Sultan Who Opened the Doors

It is worth noting that the spiritual legacy of Imām al-Ḥaddād extended well beyond the valleys of Ḥaḍramawt. The Wird al-Laṭīf and Ratib al-Ḥaddād — his litanies of remembrance — were introduced and supported within the Harams of Makkah and Madinah under the patronage of Sultan Mehmet IV (sometimes rendered Mehmed or Muḥammad IV) of the Ottoman Empire (r. 1648–1687). A ruler known for his reverence of Islamic and Sufi traditions, Sultan Mehmet IV’s endorsement ensured that the sacred rhythms of Tarīm would echo in the holiest sanctuaries of the Ummah. Even the architecture of prayer carries the trace of this inheritance.

🟫 Note on Naming & Recognition

A reader of this blog, Kitty Amina Rabbas, beautifully reflected on the significance of this verse’s placement — connecting her own reading of Sufi Sage of Arabia with the timeline of Imām al-Ḥaddād’s visit to Madinah in 1669 CE (1079 AH), during the reign of Sultan Mehmet IV.

She reminded us that, while Ottoman rulers held immense worldly power, Sultan Mehmet IV — known for his taqwā and reverence for the Prophet ﷺ — may have recognised in Imām al-Ḥaddād a spiritual authority greater than his own. That a single verse from the Imām’s poem was chosen to face outward from the Rawḍah may well be an act of humility, not mere decoration.

Section 5: What Is the Sign?

Not everyone notices the verse above the gate. Not everyone will be called to. But for those who do, a quiet spark may awaken in the heart. Shaykh Jamiel once described this line as a wick that does not even need fire to burn. The love, the longing, the witnessing — it ignites on its own, just by being near to the Real.

There are some verses that open books. Others open doors.

And then, some open hearts.

Epilogue: The One Who Watches

The Prophet (peace be upon him) said, “Indeed, in the body there is a lump of flesh. If it is sound, the whole body is sound. If it is corrupted, the whole body is corrupted. Indeed, it is the heart.”

To read the verse that faces outward is to knock gently on that heart. To remember that character is not costume, and praise is not performance. It is to walk humbly. It is to remember the One who sees in secret.

And when no one sees, know that ar-Raqīb always does.

Acknowledgement: This blog was deeply enriched by the insights and generosity of Shaykh Jamiel Abrahams, who shared the photographs, historical details, and the luminous teachings behind the scenes. His voice opened a door, and lit a candle inside.

One response to “The Verse That Faces Outward”

[…] Spiritual Resilience” – A celebration of the sonic and spiritual power of this litany🌿 “The Verse That Faces Outward” – A meditative scroll on the hidden verses engraved above the Rawḍah, and the inner legacy […]

LikeLike