Tamat: A Sacred Completion, A Living Beginning

The word Tamat has been spoken in Cape Muslim homes for generations — a word so small, yet carrying the weight of centuries of memory. It is more than a graduation. It is a celebration of sound, of presence, of a child who has taken the Qur’an into their tongue and heart, and who now steps forward to carry it into the world.

Our grandparents knew this word from Hadramaut, where the Tamat was a festival of joy and responsibility. When a child completed their Qur’an recitation, they were gathered into a seven-day procession of voices, prayers, and sweets — with flags raised high, neighbours cheering, and the whole community celebrating the future. It was never just about memorising verses, but about honouring the discipline of correct recitation, Tajweed, manners, and knowledge that could anchor a whole community.

These children wore the banus, a beautifully embroidered cloth, reserved just for Tamat days. Banners would shimmer with Surah al-Fatihah and Ayatul Kursi waving above their heads, as if to shield and guide them on their new journey. Their teachers, the elders, and even passing strangers would bless them — because everyone understood: this child will serve, protect, and live the Qur’an (based on Sheikh Jamiel Abrahams, 2025).

When Tamat Reached the Cape

When Hadrami scholars and teachers arrived at the Cape of Good Hope, they brought this deep tradition with them, adapting it to new winds and new stones. In places like District Six, Bo-Kaap, and beyond, the Tamat found fresh soil.

Cape children would gather in the masjids, reciting the final chapters they had laboured over line by line, vowel by vowel. Then they would step out, dressed in their sorbaan and medora, and walk proudly along the cobbled streets. Their path sometimes led them all the way to the Company Gardens, deep in the colonial centre of Cape Town — an act of courage and pride that seemed to say, “This Qur’an walks with us too.”

In those moments, they were not just finishing a book. They were claiming a legacy.

The Meaning of Sorbaan and Medora

The garments of Tamat still speak.

For the boys, the sorbaan is a turban, but far more — a Khirqah al-Taḥkīm, a sign of trust. It wraps the head with a promise: you are now a guardian of Qur’an, carrying its mercy and its responsibility.

For the girls, the medora — circular, beautifully embroidered in gold or silver threads — holds the same dignity. It says: Your voice, too, is worthy. Your recitation is precise. Your role is essential.

In both, there is no sense of “fashion” — only inheritance.

A Tapestry of Cape Heritage

What makes Tamat so powerful is how it weaves into a far bigger story. It stands alongside the handwritten kitāb manuscripts passed down through Cape families, and the huffādh who still recite on local radio during Muharram (VOC Khatam broadcast, 2025). It echoes in the walls of the Auwal Mosque, where Tuan Guru — himself a prisoner and Qur’an teacher — copied out the entire Qur’an from memory in chains, so that his community would not lose its light.

It whispers through the kramats encircling Cape Town, the shrines of saints and scholars who carried Islam through exile, and who insisted that education was the best shield against forgetting who we are. Many of these traditions, as documented in works like Al-Istizādah min Akhbār as-Sādah compiled by Ali bin Muhsin al-Saqqaf, travelled with Hadrami scholars to the Cape and found new expression in the garments, recitations, and community gatherings of local Cape Muslim life.

It even rests quietly in the Tana Baru cemetery, where generations of those who lived the Qur’an are buried, their tombstones telling silent stories of resilience.

Beyond Memorisation

One of the most powerful aspects of Tamat, especially in the Cape tradition, is that it was never simply about memorising words.

Children were trained in correct pronunciation, rhythm, and understanding. They were questioned on the essential knowledge of their faith, from acts of worship to everyday etiquette, and the rights and responsibilities of being a Muslim in society.

Their teachers, elders, and neighbours stood witness that these children had become competent not only in their individual acts of worship (furoodh ayniyyah) but also in their ability to serve the community (furoodh kifayah): to lead prayer, to help wash and bury the deceased, to read du‘ā for the sick, to keep society upright.

In this way, Tamat was never a personal achievement alone, but a communal guarantee of resilience.

Echoes in Bosmont

Though times have changed, the spirit of Tamat still lives on. Take, for example, the Bosmont madrassa in the 1970s, where 15 young boys and girls graduated after years of Qur’anic training. Their ceremony was called Gatmeid Koran — a name with the same spirit as Tamat.

Six boys and nine girls, only twelve to fourteen years old, stood before thousands of family members and neighbours, reciting what they had carried line by line, vowel by vowel. The hall was so full that people pressed against the windows to watch.

It was more than a prize-giving. It was a moment of pride, of hope, of handing the Qur’an over to the next guardians of its sound and meaning.

Imams and teachers from all over — including Durban, Cape Town, and the Transvaal — came to witness these children take their place in the living chain of knowledge. There was even a colourful procession through the streets, a tradition of honour that stretched all the way back to Hadramaut.

They were not just students. They were being trusted to live the Qur’an: to hold its discipline, to guard its standards of moral character, to shine it into their communities.

(Source: newspaper clipping shared by Sheikh Jamiel Abrahams, c. 1970s)

A Living Beginning: Our Echoes, Our Hope

In every child who ties the sorbaan or drapes the medora, there lives a promise. A promise that the Qur’an will not only be memorised, but lived — that its rhythms will shape how we speak, how we act, how we serve.

From the echo of Hadramaut’s processions, to the cobbled streets of District Six, to the crowded halls of Bosmont where children stood reciting before thousands — Tamat has remained a celebration of beginnings, not endings.

These ceremonies remind us that we are never alone. We stand in a line of teachers, elders, and ancestors who trusted the Qur’an to transform us, generation after generation.

As long as there is a child willing to steady their breath, to learn its melody, to carry its mercy into the world, then our communities will never be without light.

That is the heartbeat of Tamat.

That is why it will always matter.

And that is why it must continue.

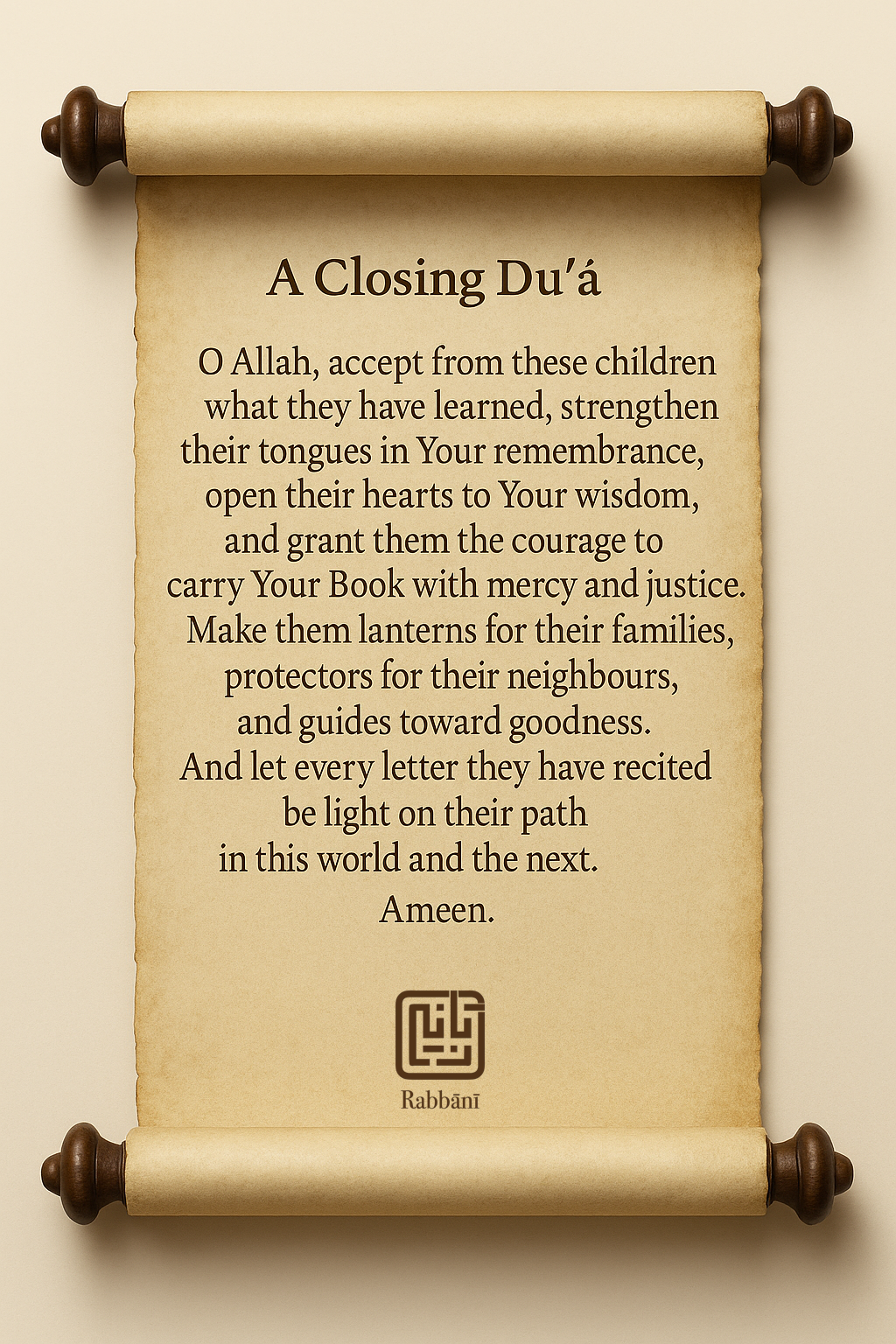

A Closing Du‘ā

O Allah, accept from these children what they have learned,

strengthen their tongues in Your remembrance,

open their hearts to Your wisdom,

and grant them the courage to carry Your Book with mercy and justice.

Make them lanterns for their families,

protectors for their neighbours,

and guides toward goodness.

And let every letter they have recited be light on their path

in this world and the next.

Ameen.

References woven into the narrative:

- Sheikh Jamiel Abrahams, Tamat, Its Origins and Objectives (2025)

- VOC Radio Cape Town annual Khatam broadcast (2025)

- Tuan Guru’s Qur’an manuscripts at Auwal Mosque (Wikipedia)

- Tana Baru Cemetery (Wikipedia)

- ourcapetownheritage.org on Cape Kramats (source)

- Aramco World, Handwritten Heritage of South Africa’s Kitabs (source)

📖 Read more at: Scroll of Sorbaan & Medora

One response to “Tamat: A Sacred Completion, A Living Beginning”

[…] 📖 Read more at: Tamat: A Sacred Completion, A Living Beginning […]

LikeLike