The Whisper of a Name

Somewhere between the worn edges of oral history and the crisp pages of archived journals, I began to trace the journey of my ancestor — Hadjie Gasanodien, also known as Carel Pelgrim. It is said he was the first Muslim from the Cape to perform the sacred pilgrimage of Hajj, sometime between 1834 and 1837, a period just after the abolition of slavery, when its wounds were still fresh. For years, his story lived quietly in our family’s memory, surfacing in fragments and whispered recollections — until now. I write to honour that legacy, to weave together the strands of fact, faith, and feeling that shaped a man, a pilgrimage, and a community still finding its voice in the aftermath of bondage.

Pilgrimage of Discovery

I first heard his name as a child, tucked into a conversation between my sister Yasmine and our aunts. Years later, Yasmine would take those threads and stitch them into a short family tree, dated July 2004. At the time, it felt like the last echo of a fading past. We had little else to go on. But something stirred in me after I returned from my own pilgrimage. A fever of purpose, a longing to know more. I began writing and publishing reflections under Al Hujjaj Magazine, not yet knowing that my footsteps had mirrored those of my own forebear, nearly two centuries earlier.

Echoes in Academic Footsteps

The name “Carel Pelgrim” returned to me unexpectedly through the work of a neighbour and friend of my father — the late Mogamat Hoosain Ebrahim, a community scholar from Primrose Park. He had long been documenting the Hajj stories of Cape Muslims. In his thesis, The Cape Hajj Tradition: Past and Present (2009), Ebrahim writes: “Hajji Gassonnodien, more popularly known as Carel Pilgrim, enjoys the distinction of having been the first Cape Muslim to have successfully completed the Hajj.” Although I first encountered his name in Ebrahim’s thesis, the full significance didn’t strike me until later — during conversations with the researcher Abdud-Daiyaan Petersen. It was through our exchanges that the identity of Carel Pelgrim truly crystallised. This was not just a figure in history — he was my ancestor. A man who left the Cape between 1834 and 1837 to walk the sacred path when few could even imagine such a journey.

It was through Ebrahim’s meticulous work that I began to understand the context of that time. Hajj was not simply a religious obligation; it was an act of defiance, endurance, and transcendence. For formerly enslaved Muslims in the Cape, to make the pilgrimage was to reclaim a spiritual identity that colonial systems tried to erase. And Carel Pelgrim, in going, carried more than personal faith — he carried the hopes of a generation emerging from bondage.

A Lineage Remembered

Abdud-Daiyaan Petersen’s research added an entirely new dimension to the story. In collaboration with Turkish scholar Halim Gençoğlu, he co-authored a paper titled Was Imam Gasanodien Carel Pelgrim an Ottoman Descendant?, published in the Bulletin of the National Library of South Africa in 2021. They explored the possibility that Carel Pelgrim may have had ancestral ties to the Ottoman world — a lineage once obscured by slavery and colonial re-naming. Through Petersen, I learned not only of the archival traces, but also of the living memory carried in Cape Town’s communities — stories that had waited generations to be heard.

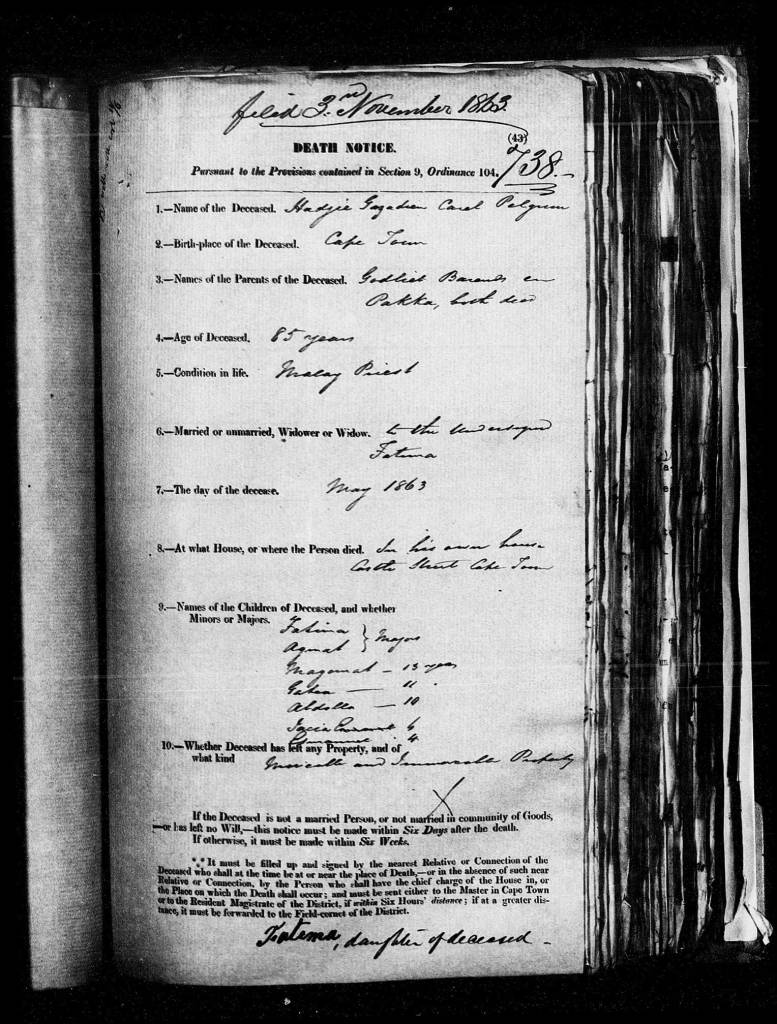

Petersen’s careful investigations, supported by old burial notices and public records, pointed with growing clarity to the fact that Carel Pelgrim and Hadjie Gasanodien — the man known for teaching Islam and the Qur’an to children in early Cape Town — were one and the same. The fragments were falling into place. What had once been academic became intimate. What had once been folklore became family history.

The Pain Beneath the Pride

The history of Carel’s mother, Pakka, adds further complexity and depth. As documented in Echoes of Slavery: Voices from South Africa’s Past by Jackie Loos, Carel — born into slavery — was the son of Pakka, a slave woman, and Jan Gottlieb Barends, a Christian man of German descent. Their relationship was informal and illegitimate, as was often the case in that era. Carel and his brother Philip inherited their mother’s status as slaves. In 1801, a notarial protocol records their transfer to a burgher, and upon his death, their eventual manumission was stipulated in his will.

Pakka’s exact identity remains debated, though one likely candidate is Janpakka of Batavia, who ran a shop in the Waterkant in the 1820s. Death records from the time, often unreliable, do not mention Carel or Philip, but their presence in community memory is clearer than archival certainty. Pakka’s story, like that of many enslaved women, survives in fragments — yet she remains the root from which this extraordinary lineage emerged. And it is here, in the shadows of that history, that I must pause. My heart aches at the likely truth: Pakka, my great-grandmother, was not loved — she was owned. The man who fathered her children, Jan Gottlieb Barends, did not protect her. He did not free her. Instead, he allowed her and their children to be sold on to another man. Was she raped? Exploited? Discarded? The records are silent, but the silence itself screams.

This is the pain we inherit alongside the pride — the wounds interwoven with the honour. In naming Pakka, I do not just trace bloodlines. I reclaim her dignity, speak her name with reverence, and acknowledge that even in bondage, she gave rise to a lineage that would one day teach Qur’an, lead prayer, and inspire generations. Her story, though faint, demands to be held — not with shame, but with solemn truth and fierce remembrance.

A Husband’s Grief

Carel’s transformation from a slave to a respected teacher, tailor, and hajji is all the more remarkable against this background. And among the most beautiful parts of his story is his deep love and reverence for his first wife, Japoera. Though she was childless, their bond was strong — spiritually and emotionally. When she passed away in their large home in Buitengracht in early 1841, Carel composed a public obituary in the South African Commercial Advertiser. It read: “The Heavenly Father, Lord of Life and Death, was pleased on the 16th instant to call from me my beloved wife Japoera, aged 64 years, 4 months and 16 days, after a happy union of [blank space] years. All who knew her virtuous character will sympathise with my loss, of which I hereby give notice to friends and relatives, requesting to be excused the visits of condolence.” He signed it: Carel of the Cape, the first Pilgrim and Priest.

In this short but poignant notice, we see not just a man grieving his beloved, but a heart refined by faith and loss. It reminds me that while history often records what men did, it rarely shows how deeply they loved. He eventually adopted the Islamic name ‘Hassan al-Din’ — appearing in records under numerous variations such as Gasnodien and Gasanodien — yet he signed himself proudly as ‘Carel Pelgrim.’ His ability to read and write in both Arabic and European script shows a deep level of literacy and determination to bridge worlds. While some have speculated that he may have spent up to three years in Makkah — a duration not firmly evidenced — what we do know is that he returned with the ability to teach Arabic and Qur’an, and left an imprint as a man of knowledge and devotion. It’s possible that his early literacy was shaped by Cornelis van der Poel, the burgher who once held legal ownership over him and later stipulated Carel’s manumission. Whether through formal tutoring or exposure to Dutch literacy, this early learning may have paved the way for his later mastery of both Islamic and colonial languages.

The directories list Carel van de Kaap as a free tailor living in Hout Street in 1816 and as a Malay schoolmaster in 1830. His brother Philip, born in 1789 and passing in 1844, was also a tailor, but unlike Carel, Philip was not a practicing Muslim. Some of Philip’s children were baptised, and in 1838 he married their mother, Carolina Marteyn of the Cape, in the Dutch Reformed Church.

Meanwhile, Carel was charting a different course. Once free, he began to prosper. In 1817, he loaned Seymen of the Cape 600 Ridollars (a substantial currency at the Cape in the early 1800s, equivalent to several months of wages for a labourer) to enable him to free his slave daughter, Cananga. By 1822, he had purchased his own home in Matfeld Lane. Then, in October 1833, Carel and his wife made a joint will, identifying themselves as the free man Carel of the Cape, alias Gaszimoedien — formerly a tailor, now a teacher in the Arabic language — and Johanna Salomonse, alias Japoera, born at the Cape.

Japoera seems to have been an exemplary Muslim wife, and Carel held her in high esteem. He set out for Mecca soon afterwards, and her encouragement must have been crucial to the success of his pioneering journey.

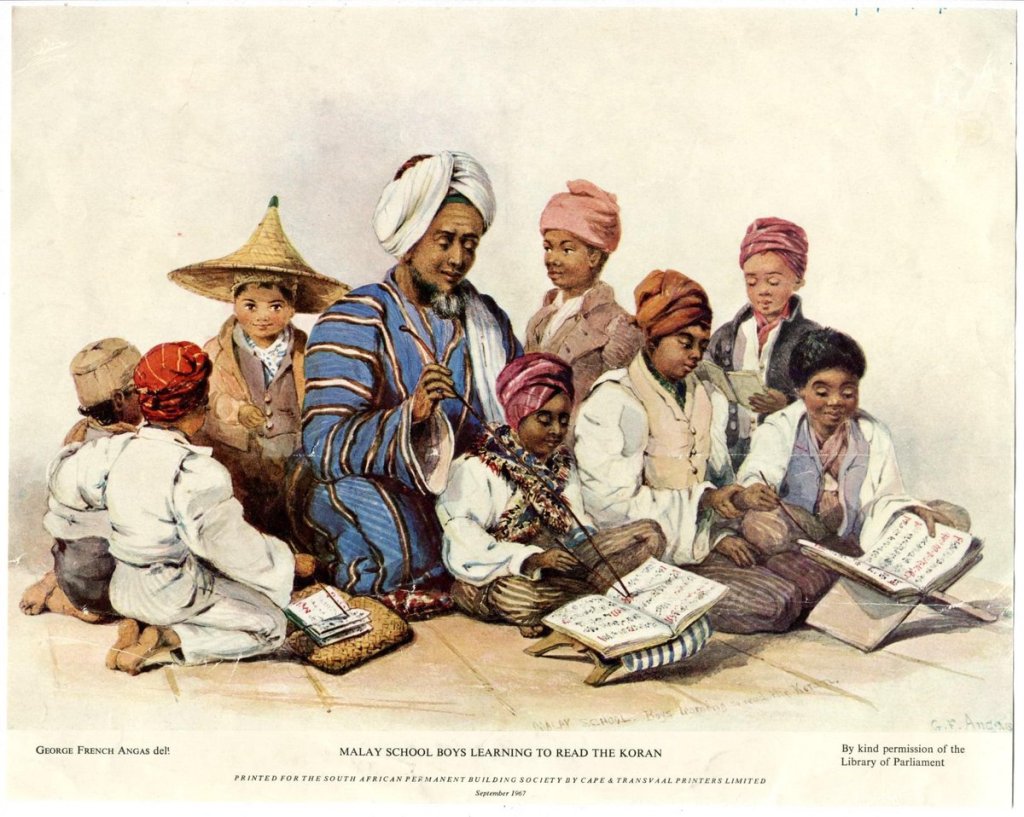

When Art Becomes Revelation

That intimacy deepened when I looked again at a familiar image — one I had seen countless times in Cape Town homes, books, and exhibitions, without ever imagining a personal connection. It is a watercolour painting by George French Angas, an English artist who visited the Cape in the 1840s. The scene is gentle but profound: a bearded man seated cross-legged, surrounded by children, teaching them the Qur’an. For years, this portrait was simply referred to as a depiction of a “Malay teacher.” But now, thanks to community scholarship and genealogical evidence, we know the truth — that teacher was Hadjie Gasanodien. My ancestor.

Another portrait, also by Angas, is held at the Castle of Good Hope in Cape Town. In it, Hadjie Gasanodien is more formally posed, with dignified composure. What amazes me most is his attire — a flowing Arabic coat, or abaya, layered over a long-sleeved thawb. The painting is filled with symbolic richness: incense burners still glowing in the frame, a minbar placed behind him as if ready for the next call to gather and reflect. To stand before that painting is to encounter the past as presence — not as myth or metaphor, but as family. His face, once anonymous to me, now echoes through mine. The ink of his story has always been part of my blood. Only now am I learning how to read it.

The Living Links

One of the most tender links between this legacy and the living was shared in Lawrence Green’s 1964 book, I Heard the Old Men Say. In Chapter Two, titled “The Living Links,” he introduces a woman named Gatea Jacobs — my great-grandmother and the daughter of Hadjie Gasanodien. In a touching passage, she recalls her father’s return from the pilgrimage to Mecca. She tells of the white robes he wore, the gentle way he taught, and how the community revered him not just as a teacher, but as a man who had seen the heart of Islam and brought its light home.

Yet there is something poignant here: on the death notice of Hadjie Gasanodien, Gatea was listed as his daughter — and she was just 11 years old at the time. Her recollections, as recorded by Green, must have been shaped not only by her own memory but also by the atmosphere that surrounded her father’s name: the reverence of others, the stories repeated in the family, the aura of a man who had left a sacred legacy. In this way, memory extends beyond personal recall — it becomes communal.

Her memories reach across generations with quiet dignity. She spoke not in grand declarations, but in lived detail — the scent of his clothes, the rhythm of his voice in prayer, the gatherings around him at dusk. Through her, his presence remained alive in the bones and breath of our family, long before any of us knew the fullness of his historical significance. It was always there — waiting for us to remember.

Incredibly, Gatea Jacobs lived nearly a hundred years, a living bridge between the earliest days of Islam at the Cape and our present time. In that same chapter, Lawrence Green recounts a remarkable scene: “One afternoon while she was still able to see and hear and talk to her family she called everyone round her. ‘I am too old to live any longer,’ she told them. Then she folded her hands as prescribed in the Islamic death ritual and passed away.” Her funeral drew thousands of mourners, and services were held in mosques across the Peninsula. It was a farewell not only to a beloved matriarch, but to an era.

Her final act — serene, faithful, and deliberate — echoed the strength of the lineage she carried. It is this spirit I now seek to honour, not only in rediscovering our ancestor, but in holding open the doorway for others to trace their own roots, to reclaim the sacredness of our past, and to remember that we, too, are living links.

Author’s Note

Written by Adli Yacubi (pen name), descendant of Hadjie Gasanodien, also known as Carel Pelgrim. This article forms part of a continuing journey to rediscover, honour, and share the stories of Cape Muslim pioneers. May it serve as both record and remembrance.

References

- Yasmine Jacobs, Jacobs Family Tree (Oral History), July 2004

- Mogamat Hoosain Ebrahim, The Cape Hajj Tradition: Past and Present, 2009

- Jackie Loos, Echoes of Slavery: Voices from South Africa’s Past, 2024

- Habib Shaikh, “First of Cape Hajis came 3 years after abolition of slavery,” Arab News, 11 October 2013

- Lawrence Green, I Heard the Old Men Say, Chapter Two: “The Living Links,” 1964

- Halim Gençoğlu & Abdud-Daiyaan Petersen, “Was Imam Gasanodien Carel Pelgrim an Ottoman Descendant?”, Bulletin of the National Library of South Africa, vol. 75, no. 2, December 2021

- Helen Swingler, “Piracy, slavery and a Mecca pilgrimage,” UCT News, 17 March 2021

- “Portraits stoke mystery of Hajji Gasnodien,” Cape Argus, 26 February 2021