Allah is Sublime.

The other day, I told my brother-in-law, Al-Ameen, how we need to promote the sorbaan again—that sacred cloth of knowledge and dignity that once crowned the heads of our teachers and storytellers. Without missing a beat, he said, “Do you want one? I’ll give you mine.”

I was taken aback. “Really? Don’t you wear it?”

He smiled. “It’s too garish for my style.”

Then he added, almost casually, “It’s from my dad. From Boeta Junain.”

And suddenly, I was no longer standing in conversation. I was nine years old again, my hand tucked in my mother’s, walking down Olifants Street in Primrose Park. We were on our way to meet my new khalifa.

My mother, Hi’ Rugaya, had decided it was time for me to learn Qur’an properly. We walked all the way down the road, right to the edge where Primrose Park brushes up against Manenberg. That place where the road thins out, where the houses change tone.

We met him at the doorway. Tall. Stern. A presence.

On the way back, she asked me gently, “So what do you think?”

I paused, looked up at her, and said with wide eyes, “Met sy grou oë en grys baard, hy lyk soos ’n wolf.” (With his gray eyes and silvery beard, he looks like a wolf.)

She laughed. But we went back the next day. And the next. And the next.

Boeta Junain became my khalifa — more than just a madrasa teacher. He taught me the Qur’an. He taught me tauhid, tahara, and how to perfect my salah. But most of all, he taught me the stories. Hundreds of them. Stories of the awliya, of lovers of God, of hidden saints, of miracles wrapped in humility.

He loved me like a son. I stayed in his madrasa well into high school. When I was seventeen, I left to study at As-Salaam Institute in Braemar, KwaZulu-Natal. There I met another teacher who helped refine my Qur’anic pronunciation. A year later, after completing matric, I came back.

And I returned to Boeta Junain.

He asked me to recite. Listened deeply. Then called his older students, saying, “Come. Let Adli help you improve your recitation.”

That day I knew what tarbiyah meant: to be raised, then trusted, then made to raise others.

Some of those students, like members of the Browns family, went on to become among South Africa’s well-known huffaadh.

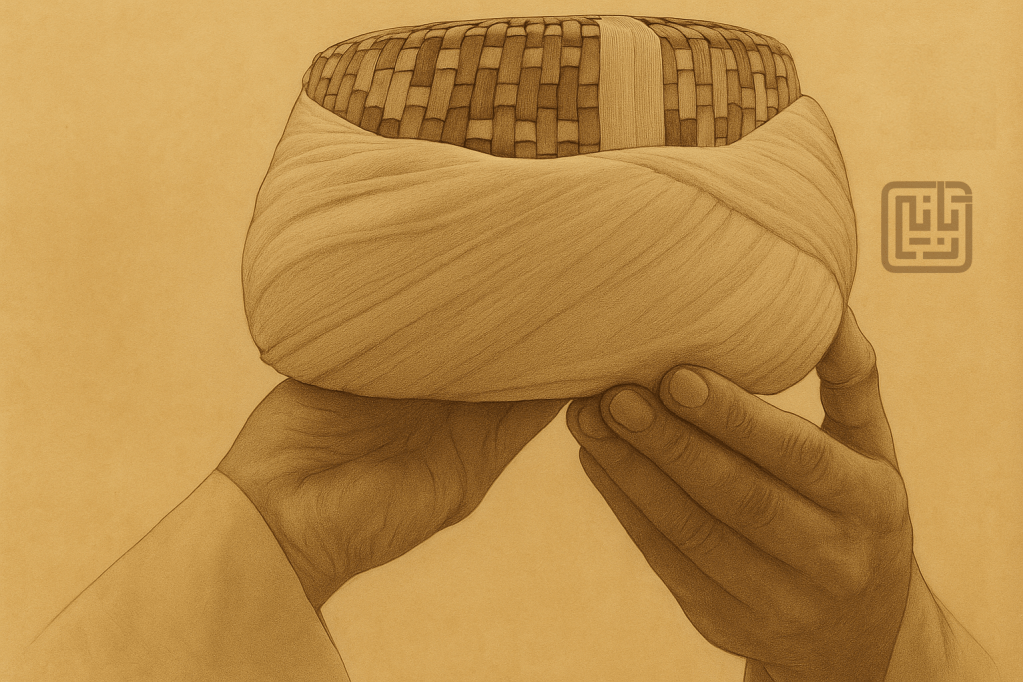

And now, all these years later, his sorbaan has surfaced again—offered from father to son, and from brother to brother. A gift wrapped not only in cloth, but in memory.

Today, three of his children, Salama, Cassiem and Juleiga are now continuing this legacy teaching young children in Qur’an and Islam.

The sorbaan is not fashion. It is not costume. It is voice made visible.

It is the texture of trust. The curve of tradition.

It says: I have received. I have remembered. I will return.

When I look at it now, even in another’s hands, I see something eternal: gold thread, cotton wrap, and the quiet humility of a teacher who looked like a wolf, but raised a whole den of cubs.

Acknowledgement

Tramakasi to Sh. Jamiel Abrahams, Sadia Fakier, Zaid Nordien, and Al-Ameen Marley — for helping carry this cloth of memory into the light.

Postscript

If Al-Ameen does send me the photo of the original sorbaan, I will share it. But even now, the memory is vivid enough to wear.