The Mother Tongue of Tasbih: Afrikaans, Islam, and the Echoes of Resistance

An Interlude of Love, Argument, and Memory

We were driving down a quiet stretch of road — just Sadia and I, the Karoo light pouring in through the windscreen, dust swirling around like old questions.

She had grown up in Worcester, her Afrikaans carefully folded by teachers and ‘ustaads’, wrapped in the formal tones of schoolbooks and sermons — so different from the swing and slang I had grown up with in the Cape.

I, on the other hand, had grown up with a different register: kombuis-Afrikaans, spoken in kitchens and mosques, spiced with Quranic rhythm and Kaapse mischief.

Somewhere between the mountains and memory, we argued.

“That’s not real Afrikaans,” she said, teasing. “You make up words.”

“And who decided what’s real?” I asked. “The Broederbond? The DRC? The state that tried to baptize us in its accent?”

She laughed — but the question lingered.

This is not just a story of a couple’s linguistic banter.

It is the story of a language born in exile, nurtured in slavery, softened by Qur’an, and carried through generations of prayer, protest, and poetry.

This is a story of Afrikaans — not as the language of the oppressor, but as the tasbih of the oppressed.

1. Afrikaans: Not a White Invention

Let’s begin here: Afrikaans was not born in Stellenbosch.

Its roots run through Cape Malay kitchens, slave quarters, mosque courtyards, and prayer gatherings beneath candlelight.

It was whispered by Javanese mothers exiled from Batavia, recited by Wolof imams from Senegambia, taught by Hadrami scribes, and softened by the Khoena tongues of this land — long before colonial grammarians arrived to cage it in rules..

The historian Achmat Davids was among the first to challenge the myth that Afrikaans was solely a “white man’s language.” His pioneering research, later extended by Hein Willemse and others, traced Afrikaans’ earliest written form to the Muslim community of the Cape — not in Latin script, but in Arabic-Afrikaans, or what was sometimes called Ajami Afrikaans.

One of the oldest surviving texts in Afrikaans is a du’a (supplication) manual written in Arabic script by enslaved Muslims.

Another is the 1869 Bayān al-Dīn, a complete Islamic catechism in Afrikaans, used for madrassah instruction.

These works prove something scholars of empire often resist: that enslaved and colonised peoples were not passive recipients of a language. They reshaped it. They sanctified it. They infused it with rhythm, resistance, and remembrance.

Afrikaans was not merely a colonial bastard tongue.

It was — and remains — a mother tongue for many, especially when that mother stood stirring boeber while reciting Qul Huwa Allahu Ahad under her breath.

2. Creole? Or Camissa?

I’ve always had difficulty with the word creole.

Not because I reject mixedness — quite the opposite. I honour our intertwined bloodlines, the sacred chaos of diaspora, the rivers that met and mingled here at the Cape.

But because the term creole, as used by certain linguists, often carries a quiet violence: it frames our language as a compromise, a simplified system born of broken tongues.

It reduces what is sacred into something stitched from scraps. As if kombuis-Afrikaans was the language of people who couldn’t speak properly — not of people who chose to pray differently.

And too often, creole becomes a coded term for “coloured.” A linguistic way of saying not-white, not-black, not-arabic, not-european — just other.

I prefer another term: Camissa.

As Patric Tariq Mellet reminds us, Camissa was the name of the river that once flowed through the Cape Flats, long before the Dutch buried it under stone. It was also the name of the Goringhaicona clan who traded with the world before colonial maps erased them.

To speak Camissa-Afrikaans is to remember we are not defined by brokenness — but by confluence.

So no, what we speak is not a creole.

It is the tasbih of the kitchen, the dhikr of the dockyard, the language of longing.

What they call kombuis, we call home.

3. The Language of Tasbih

In our home, Afrikaans was not the language of textbooks or term reports.

It was the language of tasbīḥ — of remembrance, rhythm, and breath.

Thursday nights, just after maghrib, the living room would dim into stillness. A cloth was spread. The Rātib al-Ḥaddād would begin.

First a whisper:

Qul huwa Allāhu Aḥad…

Then a swelling chorus — women’s voices, children’s murmurs, old men with trembling hands.

We called it the Gadat.

It was recited in Arabic, but held together by Afrikaans: the instructions, the rhythm, the murmured cues.

“Ouens, netjies!”

“Hou die beat mooi!”

“Moenie vinnig ry nie — luister na die kalmte.”

Sometimes, someone would break from the dhikr to hush a restless child.

“Shhh, dis nou Allāh se tyd, my kind.”

That now — that insistence that this moment of prayer was sacred and immediate — still echoes in my chest.

And when it was done, a sweetness returned:

koesisters passed hand to hand, boeber ladled with care, stories resumed in Kaaps lilt.

The tasbīḥ was complete — not just in recitation, but in the return to one another.

…

In his later years, my father told me how the elders taught Qur’an in Afrikaans before Arabic letters could be properly mastered.

Children would chant:

“Alif duwa detis, Alif duwa bowa, Alif duwa dappan, An In Oen.”

It was a phonetic bridge — an echo of how Javanese, Malay, and Arab teachers preserved tajwīd in a tongue the children already knew.

This wasn’t a lack of Arabic. It was a path to it.

And it wasn’t unique.

In Senegal, Wolof Muslims chant dhikr in their own rhythms.

In Indonesia, pegon script preserves the Qur’an in Javanese hearts.

At the Cape, Afrikaans — even in its kitchen form — became the vessel through which the Names of God entered the ears of children.

Afrikaans was never just a tool of survival.

It was a tool of transmission.

Of tawḥīd in a tongue our mothers understood.

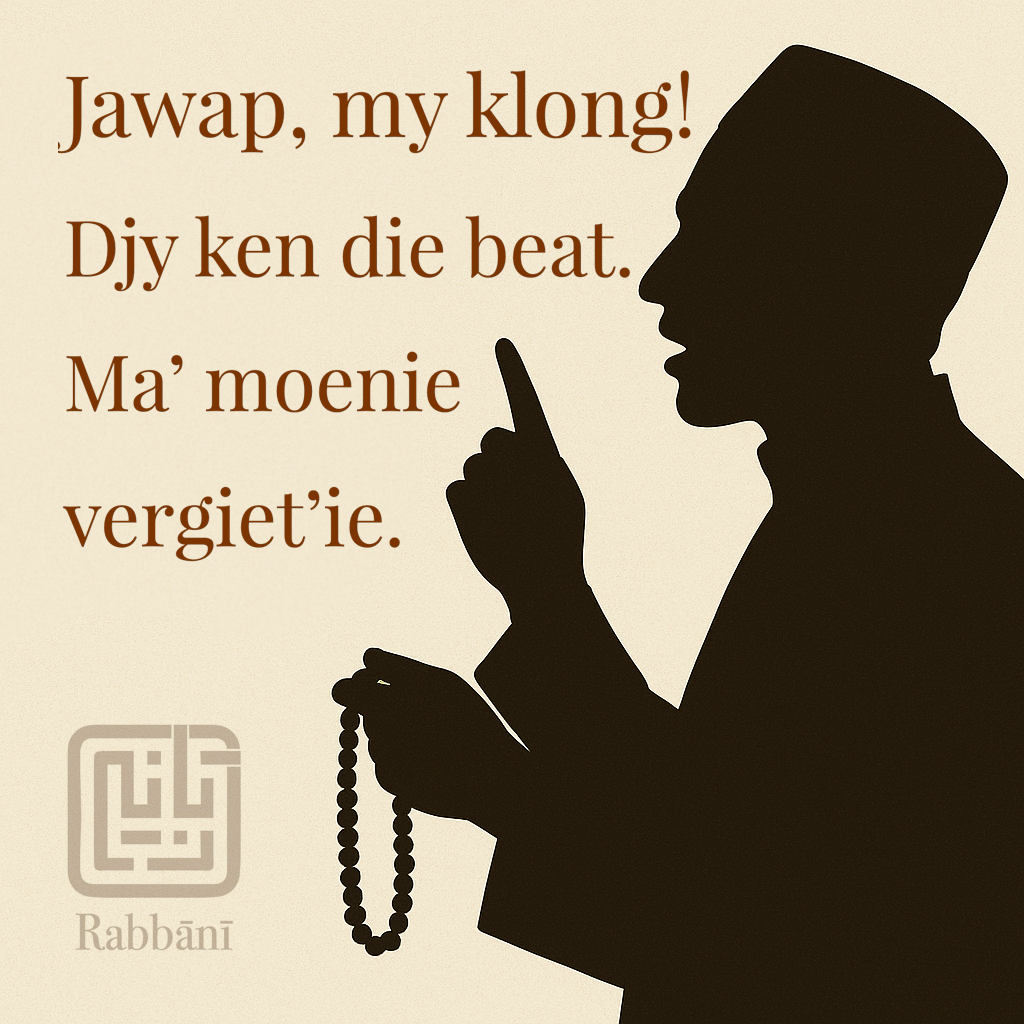

4. Jawap: The Command to Recite

In the old madrassah, silence was not golden — it was a gap in the chain of transmission.

A break in the rhythm.

A forgetting.

And so, when your voice faltered or your memory stalled, the mu’allim would lean forward — not with cruelty, but with urgency — and say:

“Jawap, my kind!”

Not shout. Not plead. But command.

Recite.

Respond.

Step back into the rhythm.

Because in the Cape, jawap was never just “answer.”

It was a summons — to speak, to return, to carry what you’ve been given.

The word comes from the Arabic ج و ب — jawāb, meaning “reply,” and ijābah, the act of answering a call.

But in Afrikaaps, jawap widened its reach.

It meant:

- Recite the ayah.

- Step into the beat.

- Don’t let the tasbīḥ fall silent.

You could hear it outside the masjid too —

In a kitchen when someone moved too slow:

“Jawap nou! Die kos gaan brand!”

In a playful quarrel between siblings:

“Ek wag vir jou jawap, dan sal jy sien!”

But the root remained sacred.

To jawap was to not let the memory die.

It was to pull the verse from the chest, even if the chest was tight.

It was to let the breath carry the Names of God, even when the tongue stumbled.

…

Some nights, I’d sit with my father as he corrected a cousin’s recitation.

He never raised his voice.

Just waited for the right moment and said, gently but firmly:

“Jawap, my klong! Djy ken die beat. Ma’ moenie vergiet’ie.”

That sentence lives in me.

And I wonder now if that’s what the Qur’an itself asks of us:

Fa-ijībū li…

So respond to Me… (Qur’an 2:186)

Not just with belief, but with voice.

Not only with intellect, but with breath.

To live is to jawap.

To remember is to jawap.

To teach, to protest, to praise — is to jawap.

And maybe that’s why the Gadat still echoes through the Cape —

Not because we’ve mastered every rule of tajwīd,

But because someone once told us:

“Don’t keep quiet. Jawap.”

To live is to jawap. To resist is to remember what we’re made of.

5. Echoes of Resistance: A Language That Refused to Die

To speak Afrikaaps was once considered vulgar.

Uneducated. Low.

The language of skollies, meidens, and kitchen girls.

The official line was clear: proper speech belonged to white mouths and white pulpits.

But at the Cape — in Salt River, Bo-Kaap, Parkwood, Belhar, and Bonteheuwel — our people spoke tasbīḥ in their own tongue.

And that was resistance.

They recited Qur’an with Kaapse inflections.

They sang dhikr in alleyways, under washing lines, between the Sunday curry and the Monday washing.

They wrote duʿāʾ in Arabic script — with Afrikaans vowels — because the state’s education system wouldn’t teach them Arabic, and the imām couldn’t write Latin.

This wasn’t survival. It was sovereignty.

When the tongue of the oppressor tried to rename us,

we jawapped back with remembrance.

When they broke our schools,

we turned kitchens into classrooms.

When they mocked our accent,

we sharpened it into poetry.

And in that echo, you can still hear the names of the early reciters:

Tuan Guru teaching on Robben Island.

Imam Saban writing Bayān al-Dīn for the children of slaves.

Ouma Gatie sitting in her chair, reciting Yā Sīn in Afrikaans until her teeth ached — and her soul rose light.

Even Apartheid’s Bible — the 1933 Afrikaans translation — couldn’t erase the sound of tasbīḥ in our streets.

Because we had our own Book, our own rhythm.

Our mothers wrapped Qur’an verses in the same cloth they wrapped around your lunch tin: tight, warm, enough.

…

To remember in Afrikaans — to teach La ilāha illā Allāh with a Cape tongue — is not just a cultural artefact.

It is a form of sabr.

Of jihād.

Of wilfully remembering what empire tried to make us forget.

And so even now, when I hear a child reciting in Afrikaaps,

I don’t correct the accent.

I listen for the memory in the melody.

Because sometimes, the resistance is not in the grammar —

It’s in the breath.

Theatre as Tasbīḥ: Walking Through 333 Years

In 1986, the Call of Islam commemorated 333 years of Islam in South Africa — not with a speech, but with a play.

“A Walk Through 333 Years” was a theatrical act of remembrance: combining Qur’anic recitation, storytelling, song, and dramatic re-enactment of Muslim life from enslavement to resistance.

Directed by a community professional, informed by the late Achmat Davids’ research, and carried by a cast of ordinary believers, the play jawapped our history with full breath. It wasn’t just performance — it was pedagogy.

The production travelled across the country and left audiences moved in ways no pamphlet or sermon could match.

Like tasbīḥ in the kitchen or dhikr in the alleyway, this was language at work — resisting, remembering, reclaiming.

Because sometimes, the resistance is not just in the grammar.

It’s in the gathering.

It’s in the jawap.

It’s in the walk through our own years — together.

6. Tongue, Tasbīḥ, and the Right to Return

So what is a language?

A dictionary will tell you it’s a system. A grammar. A structure of rules.

But we — the people of kombuise and kramats, of ratibs and roti —

we know different.

We know that a language is also a holding.

A way to wrap memory is like a salomie wrapped in a roti — not for perfection, but to preserve warmth.

We know that Afrikaans is not only the language of the jailer — it is also the jawap of the jailed.

It is the rhythm of the Qur’an under colonial roofs.

It is the sound of mothers whispering Bismillah while brushing a child’s hair.

It is the beat of “Moenie vergiet’ie” — not as a threat, but as a prayer.

If they ask us who we are, we might say:

We are the children of those who answered with breath when the world tried to silence them.

We are the ones who recited even when we could not read.

Who made dhikr in a tongue they said was impure.

Who kept the memory of revelation alive —

in kitchens, classrooms, corners of mosques, and hearts that stammered but never surrendered.

…

And so, if anyone asks:

What kind of Afrikaans is this?

Tell them gently:

This is not the Afrikaans of the oppressor. This is the mother tongue of tasbīḥ. The language of jawap. The rhythm of remembrance. This is the tongue that taught us to speak back to the silence — and return to God with our own breath, in our own way.

Because what they called kombuis,

we called home.

📚 Footnotes & References:

- Achmat Davids, The Afrikaans of the Cape Muslims from 1815 to 1915: A Socio-Linguistic Study, UCT PhD Thesis, 1987.

Foundational in establishing the role of Arabic-Afrikaans and Cape Muslim literacy practices. - Hein Willemse, editor and scholar of Afrikaans literary traditions, particularly around marginalised and non-standard variants.

Relevant essays include: “Language, Race and Power in South Africa.” - Patric Tariq Mellet, The Lie of 1652: A Decolonised History of Land, and various writings on Camissa identity and language reclamation.

- Adli Jacobs, Punching Above Its Weight: The Story of the Call of Islam, Function Books, 2024, p. 84.

Documents the Call of Islam’s 1986 theatrical production “A Walk Through 333 Years”, co-developed with historian Achmat Davids. This performance combined Qur’anic recitation, song, and drama to embody the memory of Islam’s journey from slavery to resistance in South Africa. - Qur’anic verse cited:

Qur’an 2:186 — “So respond to Me (fa-ijībū li) and believe in Me, that they may be rightly guided.” - Oral traditions and family sayings (e.g. “Jawap, my klong. Jy ken die beat.”)

Attributed to the author’s father, part of Cape Muslim living heritage. - Arabic-Afrikaans manuscripts (e.g. Bayān al-Dīn, Ratib al-Ḥaddād in Arabic-Afrikaans):

Refer to holdings in the National Library of South Africa, Clarke Estate Mosques, and private Cape Muslim collections. - Laagu vs Tajwīd debates and Thursday night Gadat gatherings:

Drawn from oral sources and lived practice in Cape Town’s Muslim communities.

May cite the influence of Shaykh Seraj Hendricks, Imam Taha Gamieldien, and Imam Abdullah Haron’s legacy of fusing dhikr with defiance.

🪶 Related Articles in This Series:

- The Forgotten Tongue of Remembrance

A reflection on Arabic-Afrikaans, the erased voices of dhikr, and the linguistic tenderness that survived colonial erasure. - The Ratib al-Haddad: A Symphony of Spiritual Resilience

Traces the journey of the Ratib from Hadhramaut to the Cape, focusing on collective remembrance and melodic resistance. - Tamat: A Sacred Completion, A Living Beginning

Explores the Cape Muslim tamat ceremony as both rite of passage and living echo of West African, Javanese, and Arab pedagogical traditions. - From Chains to Qur’an: The Cape’s First Pilgrim and My Bloodline

Uncovers the journey of Hadjie Gasanodien (Carel Pelgrim), the first recorded Cape Muslim to perform Hajj — linking personal ancestry with collective emancipation.

4 responses to “The Mother Tongue of Tasbih: Afrikaans, Islam, and the Echoes of Resistance”

Very beautifully written Māshallah!

LikeLike

Shukran Fatima — your words mean more than you know. May the barakah of our mother tongues continue to echo, in resistance and remembrance. 🤲🏽🕊️

LikeLike

very insightful

LikeLike

Shanaaz, your words—“very insightful”—reach deep. The Mother Tongue of Tasbih: Afrikaans, Islam, and the Echoes of Resistance is an attempt to listen for those quiet threads connecting language, memory, and faith across generations. I’m grateful that the insight resonated with you. May the echoes of our shared histories continue to inspire remembrance, resilience, and the courage to speak in all our mother tongues.

LikeLike