Our Father: Braima Winter — The Man Who Read the Weather and Raised Us with Words

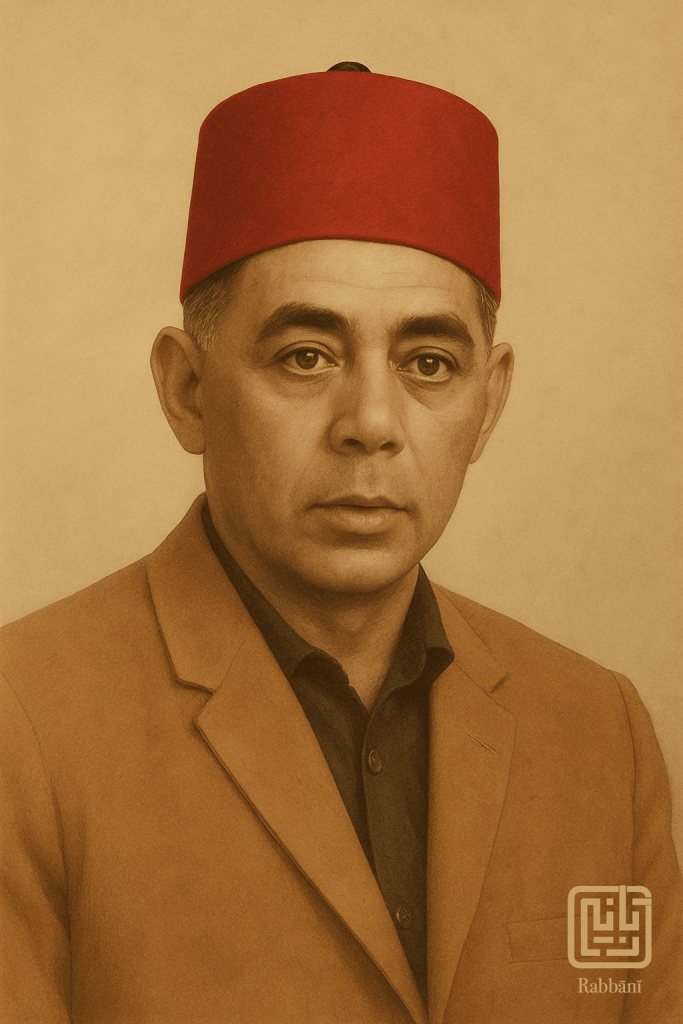

Braima in His Red Koefiyya

Not just a head covering, but a hush of dignity.

A crown worn by those who build without boasting,

who read clouds like verses,

and raise children like minarets —

quietly, steadfastly, towards the Light.

They called him Braima Baard.

But he was clean-shaven.

They called him Braima Winter.

Because even if there was only one cloud in the sky, he’d say: “Dis winter, Gaya.”

He was our father: Ebrahim Abdul Aziz Jacobs.

Born of tailors and dressmakers — his father, Abdul Aziz, worked with thread; his mother, Gadija, crafted fabric into form. From such soft-handed lineage, he turned to bricks and cement.

His mother once teased him, laughing:

“Met jou sag handjies, wat soos ‘n bricklayer gan djy maak?”

But he became one. And not just any bricklayer.

He built kilns. He protected cement floors. He shaped the foundations that others would walk on long after he left the site.

He built a good few walls of Primrose Park masjid (called Jamiya Tus Sabr).

He guided others. Trained them. Gave them skills, and more than that, dignity.

Yet behind all of this physical work was another kind of labour — of language, of laughter, of letters.

He was the spine of our family’s love of books, storytelling, and sly, gentle humour.

He was reading before most could walk. As a child, already in his diapers, he was immersed in words, letters, pages. No one had to push him. It was in him.

Imam Ghazali. Ibn Battuta. Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī. Shams Tabrizi.

He didn’t just read. He remembered. And retold. And spun.

He raised seven children with his hands, but never truly raised his hand at them.

His discipline was the silence between sentences.

His presence was the lesson.

We never feared him. We trusted him.

Because the man who knew where every cloud was going — also knew how to hold a storm.

He didn’t build palaces.

He built people.

He built us.

And when he dressed, he often wore his red koefiyya — not the long turban of his childhood, but a shorter, neat fez with a tassel, worn by men who held pride without noise. It was the kind worn by many hadjies after the sorbaan had fallen out of fashion. It became his crown.

One Fajr morning, when I was a teenager, he woke me gently. We walked together through the streetlights of Primrose Park toward the mosque. I looked around and said, “So many Muslim houses still have their lights off. Don’t they make salah?” He chuckled softly, and said, “Perhaps they are praying while their lights are off so that they can go back to sleep. You must focus on your own salah. Other Muslims are not your concern.”

And perhaps this was the secret of his laqab…

As Shaykh Jamiel Abrahams reflected:

“The secret of this Laqab… is that no Winter will pass except that he is Madhkour — remembered — even by the non-living creation. Better than making dhikr, he becomes Madhkour — mentioned and remembered — by his Rabb.”

May Allah grant us all to become Madhkour.

Āmīn.

“What a lovely man. He was always saying to us, ‘Kom biesmielah,’ and happy to have us around.”

— Shamiel Isaacs, Bonteheuwel (Call of Islam)

And today, as we recite stories, as we reach for bricks and books and blessings — we say:

Braima Winter, we remember.

And we still feel your weather.

And your words.

And your mercy.

Innā li-llāhi wa-ʾinnā ʾilayhi rājiʿūn

Surely to Allah we belong and to that we will return. [Surah Baqarah, 2:156]

And this is how we remember him best:

Laughing beside Gaya, the love of his life —

as if the whole world had just whispered a joke only they could understand.