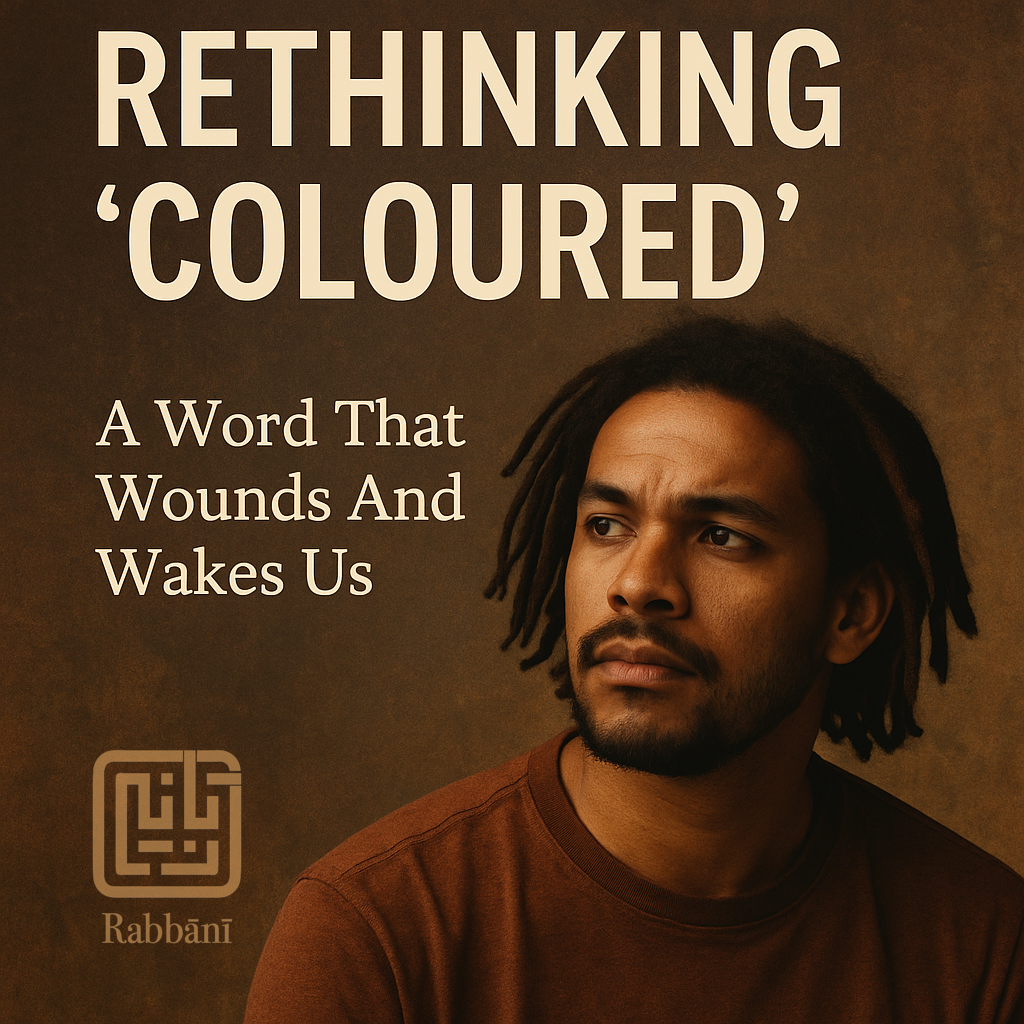

🟤 A Word That Wounds and Wakes Us: Rethinking “Coloured” in the Age of Memory

By Adli Yacubi

“The name ‘Coloured’ was forcefully given to us.”

— Glen Snyman, Sunday Times, 20 July 2025

Last Sunday’s front page posed a question still burning through our national psyche:

“Coloured: A term to ban or build around?”

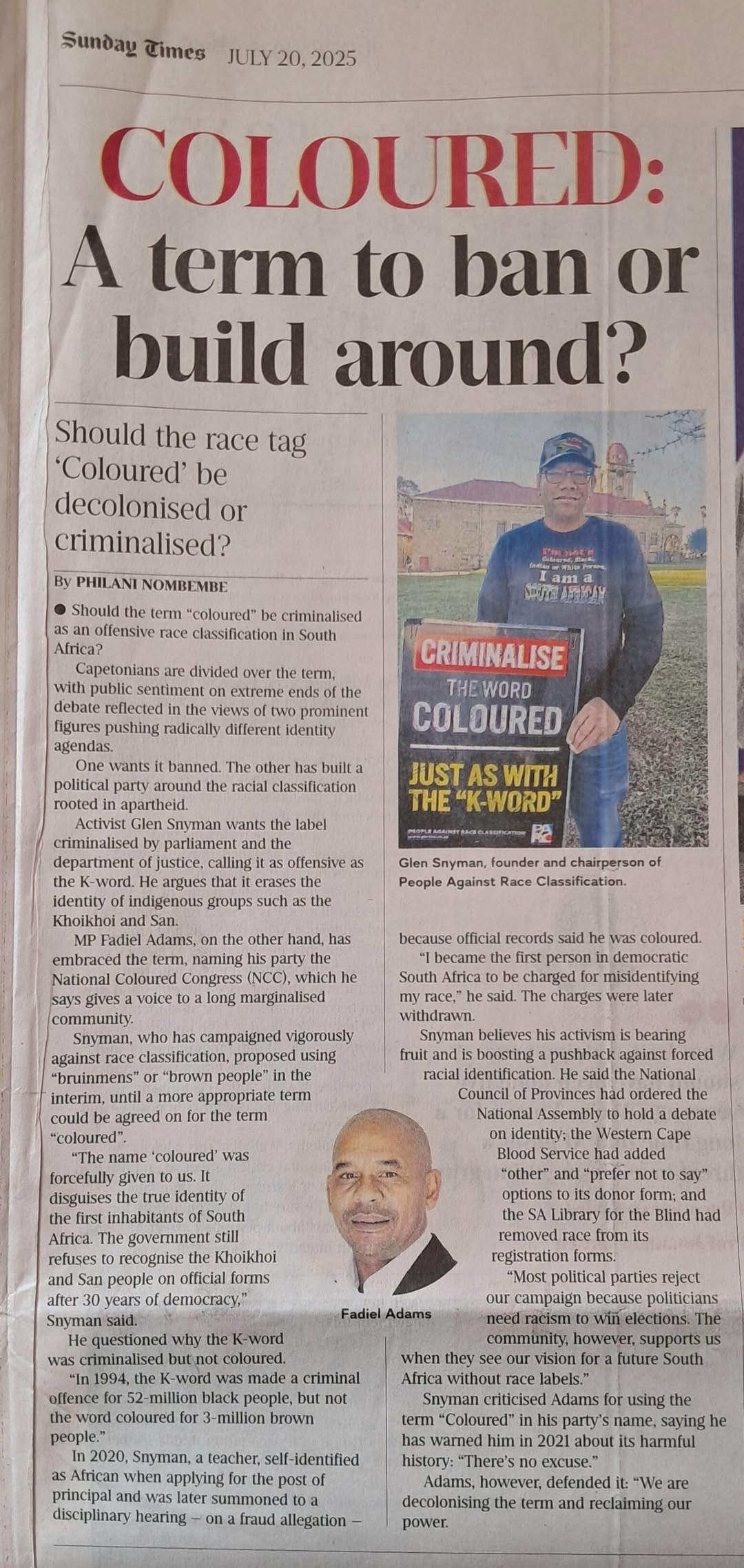

In bold red and black, the Sunday Times article (20 July 2025) captured a moment of deep fracture — and opportunity. It spotlighted the voices of two public figures, Glen Snyman and Fadiel Adams, whose opposing stances on the term “Coloured” reflect long-simmering tensions within post-apartheid identity politics.

And yet, beyond the noise, a different current is rising. One that calls not for renaming or romanticising, but for remembering.

❌ Criminalise or 🔁 Reclaim?

Glen Snyman, founder of People Against Race Classification (PARC), argues that “Coloured” is not merely outdated — it is damaging, like the K-word:

“It disguises the true identity of the first inhabitants of South Africa. The government still refuses to recognise the Khoikhoi and San people on official forms after 30 years of democracy.”

Snyman’s activism led to national debates in parliament and institutions like the Western Cape Blood Service adding the “prefer not to say” option to racial forms. But his call for criminalising the term has stirred legal and ethical challenges — and provoked a backlash from those who feel erased by the erasure.

On the other end stands Fadiel Adams, leader of the National Coloured Congress, who says:

“We are decolonising the term and reclaiming our power.”

Adams believes in building around the identity — anchoring it in lived pain, community resilience, and political recognition. But critics say this collapses our histories into apartheid boxes, reinforcing labels that were never ours to begin with.

🪶 What’s In a Name?

Into this fire, Patric Tariq Mellet, historian and author of The Camissa Embrace, offers clarity beyond polemics:

“Goringhaicona was never a name people used for themselves. It was a derogatory Dutch term meaning outcast or scavenger. Autshumao’s people were known as the /Kamisons — water traders. They were a sub-group of the Cochoqua. The term Camissa remembers them not as fragments, but as a river of convergence.”

Mellet’s contribution is not merely semantic — it’s genealogical. It reveals that terms like “Coloured” and even “Brown” are colourist overlays that flatten our multiple ancestries: San, Khoe, Xhosa, enslaved African, Indian, Javanese, and European.

His critique of both Snyman and Adams is incisive:

“Both men reflect valid concerns — but both are caught in Apartheid’s trap. One criminalises. The other romanticises. Neither steps fully into the radical work of remembering, beyond state classification.”

🧬 Memory as Resistance

To stand in this in-between space — neither erasing the term nor enshrining it — is to do the work of memory. To say: we were misnamed, but we are not unnamed. We are more than what apartheid called us. And we are not only what the census categories offer us.

This blog, like others before it, is not a position paper. It is a growing reflection rooted in questions I’ve been asking for years:

— What do we mean when we say “I am Coloured”?

— Who gets to say so?

— And what happens when our ancestors whisper different names?

We are not “non-white.” We are not “Other.”

We are not “Coloured” in the way the law intended.

And we are not simply “Brown,” either.

We are Camissa. We are from the river.

We are still flowing.

📝 Postscript

We acknowledge the work of Patric Tariq Mellet, whose scholarship challenges colonial erasure. Through his writing, Camissa is no longer hidden — it is remembered as a place of sweet waters, of creolised identity, of sacred convergence.

His reminder to not confuse / reclaim / romanticise pejorative colonial terms (such as “Goringhaicona”) is especially important — and will be reflected in our future revisions.

We also draw from Stuart Hall, who wrote that nations are “narrated into being.” To say “I am from Camissa” is to resist imposed categories and to speak from the riverbed of relation — to narrate the nation otherwise.

The story of who we are is still being written. Let it not be in the language of our conquerors — but in the voice of our rivers, mountains, mothers and names.

💧 The Colour of God

صِبْغَةَ ٱللَّهِ ۖ وَمَنْ أَحْسَنُ مِنَ ٱللَّهِ صِبْغَةًۭ ۖ وَنَحْنُ لَهُۥ عَـٰبِدُونَ

“This is the colour of Allah. And who is better than Allah in colouring? And we are His worshippers.” (Qur’an 2:138)

Not the colours of empire. Not the names imposed by maps or ministries.

But the silver sap beneath the bark. The scent of rain on root.

This is the ṣibghah of God. The sacred dye of those who remember.

📎 Read the full Sunday Times article: “Coloured: A term to ban or build around?” (20 July 2025)

🧭 This story flows alongside others:

– “The Mother Tongue of Tasbih”

– “From Chains to Qur’an”

– “The Legend of the Silver Tree”

2 responses to “A Word That Wounds and Wakes Us: Rethinking “Coloured” in the Age of Memory”

[…] → A Word That Wounds and Wakes Us: Rethinking “Coloured” in the Age of Memorywhich wrestles with the term “Coloured” — its violence, its survival, and the sacred dye of remembrance:ṣibghah Allāh — the Colour of God (Qur’an 2:138). […]

LikeLike

Asalaams Br Adli Once again, thought provoking manuscript Adli…Ma’ShaAllah. Our Master said-” Verily Allah Almighty is beautiful, and LOVES beauty” One of HIS 99 names is AL-JAMEEL, beautiful patience, SABRUN JAMEEL… Therefor, it depends on how and what is my understanding of the term beautiful .. Of pragtig of mooi…is it the colour black, white, pink, purple, brown, beige, off white, cream, top-deck lol, etc In conclusion…who am I…a “beautiful coloured” hailing from the then CAPE of GOOD HOPE…Ma’ShaAllah… Algamdulillah Sr Kulsum

>

LikeLike