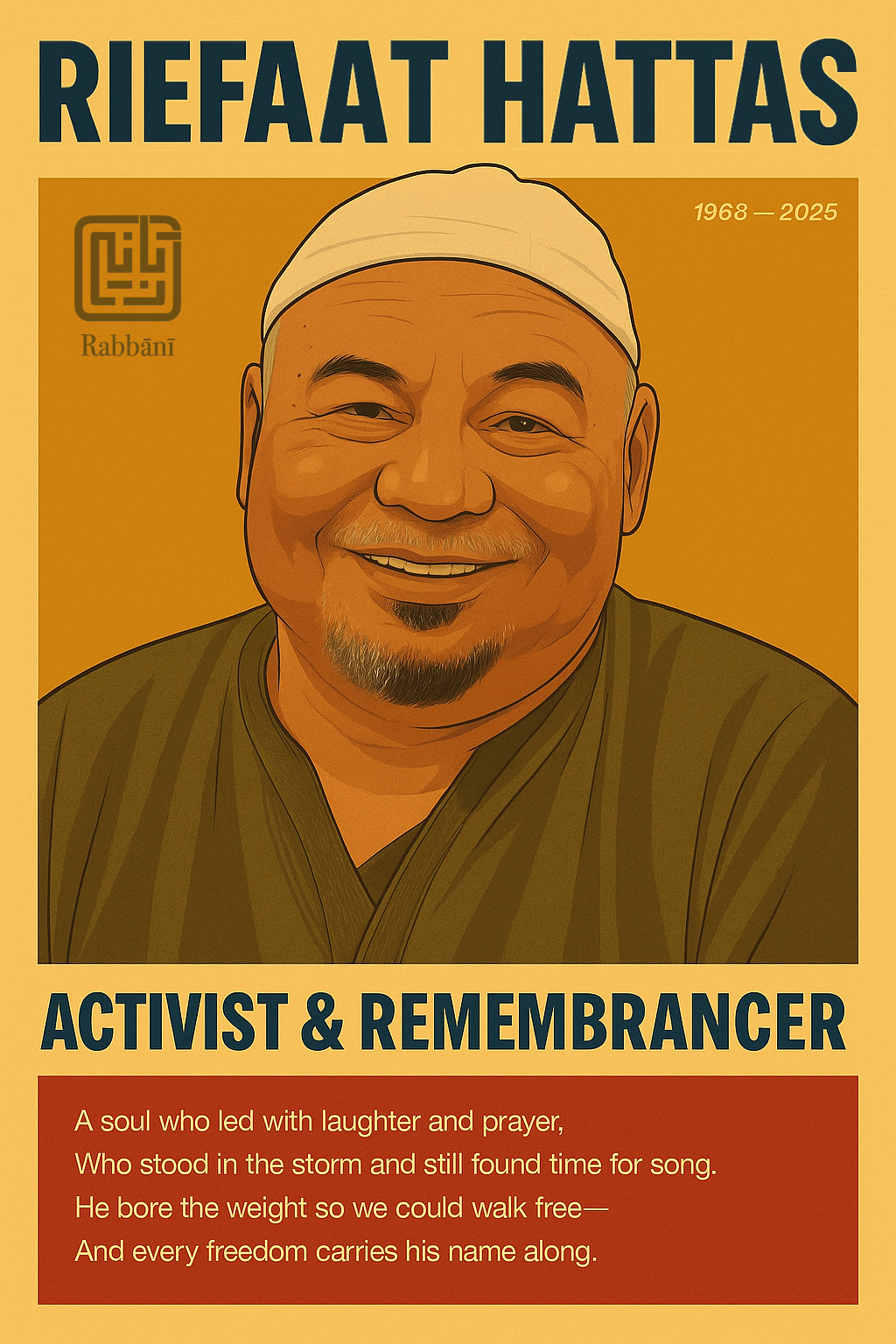

The Boy Who Waved Back: Remembering Riefaat Hattas of Manenberg

Riefaat Hattas, second from top right, stands among friends and comrades — a generation brimming with laughter, courage, and purpose. [Pic: Yunus Mohamed]

Manenberg: Where Struggle Learned to Laugh

There’s a photograph from another time — a car crowded with boys and brothers, some perched atop, some packed inside, all lit by the unmistakable fire of youth. Manenberg, 1980s: a borrowed car, a shared cause, a city holding its breath.

Among them is Riefaat Hattas — eyes forward, a quiet anchor in the rising tide.

Those who lived through the 1980s on the Cape Flats will remember:

Cars that carried more than passengers — they carried dreams, sometimes fugitives.

Boys who became men before their time.

Smiles that defied a brutal state.

It was here, at Silverstream, in schoolyards dusted with chalk and hope, that Riefaat found his voice.

A student leader, a Call of Islam activist, he joined a movement that dared to speak justice in the language of faith.

A Life Shaped by Struggle

Riefaat Hattas was born in 1968 and grew up in Manenberg, places shaped by apartheid’s sharp edges and the stubborn dignity of ordinary families. He matriculated at Silverstream Secondary in 1986, a year that would change his life and the country.

That year, he led a student march — Casspirs ringed the school, hundreds of unarmed students brutalized by the SADF.

He was only 18 — but already a leader, a UDF and ANC supporter, mentored by Celeste Naidoo and MK underground structures.

In November 1985, during a march to honour detainees and the fallen, Riefaat was arrested under the Terrorism Act.

Tortured at Manenberg station, interrogated, violated, broken down — then sent to Victor Verster Prison.

“The National Party should take responsibility for destroying and ruining our lives.”

— Riefaat Hattas, TRC Hearings, 1997

Testimony and Trauma

Riefaat’s scars ran deep, but he spoke them aloud at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission:

“We aged ten to fifteen years in a matter of months… We never realized the kind of psychological stress and trauma we have been subjected to… I’m messed up because of what I went through during my high school days.”

He admitted the cost:

Nervous wreck, unable to finish school in a normal way. Many friends became casualties — some went into hiding, some fled, others fell into drugs or gangs.

Riefaat himself needed weekly counseling to manage the trauma that never left.

“Money can put something meaningful into my life. I have been tortured, I have nightmares, I could pay for counselling.”

Action Without Fear

Those who knew him say he was action-oriented, never content to sit on the sidelines.

He became known for his directness, for “not being afraid.”

He worked as a professional assistant officer for the City of Cape Town, always serving — quietly, sometimes with a smile that held both pain and possibility.

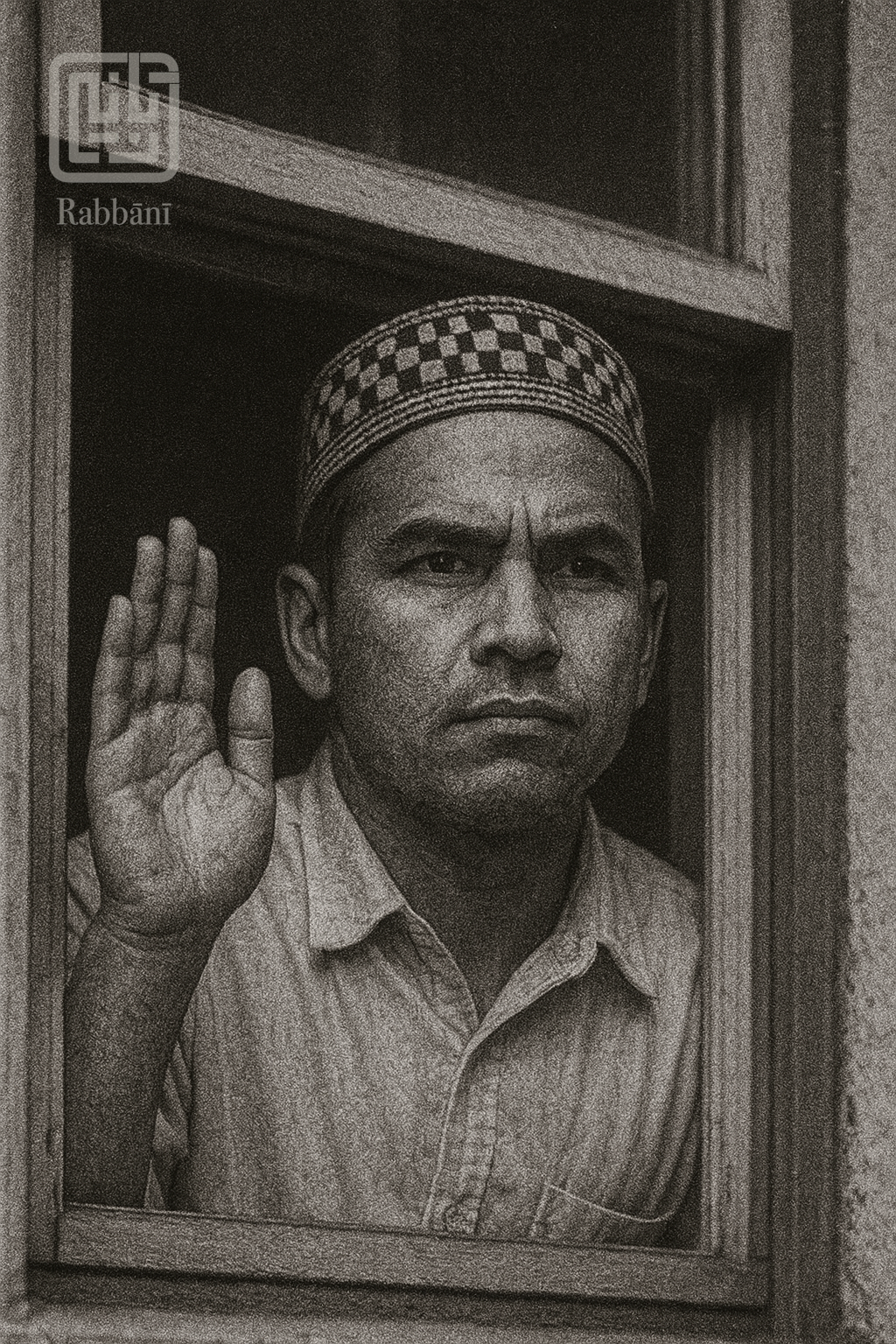

This scene — recreated in tribute — echoes the iconic image of a young comrade who refused to disappear, even when others scattered.

Another time, he famously waved from the window of the American embassy during a similar protest. That photo is still an icon: the boy who refused to disappear.

Legacy: The Freedoms We Now Inherit

The freedoms Cape Town’s Muslims (and South Africans in general) enjoy today — to gather, to pray, to march, to speak — were won by Riefaat’s generation at terrible cost.

“We never knew how big our contribution would become, how our struggle would free so many others.”

So said a comrade at his janazah, echoing Ebrahim Rasool’s words.“He was one who stood out for justice as a witness to Allah. Riefaat carried the scars of torture and never broke — he stood in the embassy window, waving, so we would know not to run. The freedom we have today was won by his courage and the courage of his generation. Let us not pray perfunctorily; let us remember what was paid for us.”

Stories now echo from one generation to the next.

Medat Adams’ young son hears the “old days” — torture, detentions, the moppies that kept hope alive when hope seemed like madness.

Riefaat was a storyteller, a writer of comic skits for the nag troop, a keeper of laughter in the midst of struggle.

Riefaat: Lightness in the Struggle

At rallies and mass meetings, Riefaat was always the one looking for a piece of cardboard — anything, just to make salaah on, wherever he found himself.

During the matric exam boycotts, a group of them hid out at a teacher’s house. When the teacher came out, he called, “I can see you, Achmat!” — because Achmat was so tall, he couldn’t hide behind a bush.

After court appearances, Riefaat would lead the hungry crew straight into a janazah house along Thornton Road — knowing there would always be food, and never standing on ceremony.

Once, passing Pollsmoor Prison, he hung out the car window and led everyone in shouting, “Viva Mandela!” At the drive-in later that night, seeing white kids lugging their mattress home, he yelled out, “Sê ve jou ma — jy’t ’n comrade gesien!” [Tell your mom that you saw a comrade!]

He had a gift for turning every moment — even hunger, boredom, or fear — into a kind of resistance and joy.

#masekin — Ma se Kind, My Mother’s Child

Not just the humble, not just the poor —

but every child of the Cape,

every struggler, every brother, every sister

carried in the memory of mothers

who gave more than they had,

who called each of us masekin —

my mother’s child,

so no one would feel alone.For Riefaat, it was the truth of his life:

He belonged to the people,

and the people belonged to him.

Legacy: Freedom, Memory, and Sacred Song

But Riefaat was also a keeper of remembrance.

Who can forget the play, 333 Years of Islam in South Africa?

He wasn’t just a participant — he was central, guiding the theatre piece, leading voices through the opening invocation.

He would start the Ratibul Haddad, and his voice — deep, insistent — would call out “Qul huwallahu ahad…” until the whole circle answered.

He loved the Gadat, cherished the sacred rhythms that stitched community and soul together.

These weren’t performances; they were living acts of ibadah, of memory, of survival.

Riefaat made sure that in our struggle, we didn’t forget our dhikr, our poetry, our song.

It’s no wonder he led the Gadat like he was born to it —

his Hattas (Attas) blood remembering the names

that sailed from Hadhramaut to the Cape.

Barakah doesn’t always skip a generation;

sometimes it lands on the tongue of a child who never forgot.[The Attas (Al-Attas) family are a Hadhrami lineage whose spiritual traditions—like the Ratibul Attas and the Gadat—helped shape Cape Muslim remembrance.]

Still carrying the light, the smile, and the steadfastness that defined his youth.

A witness to history — and a reminder that joy is its own act of resistance.

Legacy at Work: Community Builder in the City

After the struggle, Riefaat entered the City of Cape Town at the most basic level in the electricity department — but he never stopped building. According to Farouk Robertson (Communications, City of Cape Town), Riefaat steadily worked his way up to become central in community education for the City’s energy cluster. He was a true driver of interdepartmental, community-facing initiatives: creative, innovative, and never afraid to challenge technocrats to see things from the community’s point of view. He didn’t just serve; he inspired — often sharing new approaches and championing programs that brought real, active engagement into the City’s work.

Even in the workspace, he was a man of progressive action.

(Thanks to Farouk Robertson, via Shamile Manie, for these memories.)

Closing Prayer

May Allah gather Riefaat among the steadfast.

May his wounds be healed in the gardens of peace.

May we remember him — in our freedoms, in our laughter, in every act of justice — as the one who waved back when the world turned away.

Tramakasi — Our Thanks

This tribute would not have been possible without the memories, love, and testimony of those who knew Riefaat best.

With deep gratitude to Ambassador Ebrahim Rasool, Shamile Manie, Salih Davids, Medat Adams, Dawood Hattas, Zieyaat Hattas, and the rest of his dear family — for their witness, their courage, and their generosity in holding Riefaat’s story with both pain and pride.

May Allah bless you all. Tramakasi. Shukran. Thank you.

References & Further Reading

Oral Tribute:

Ebrahim Rasool. “Janazah Tribute for Riefaat Hattas.” Delivered at Riefaat Hattas’s janazah, July 2025. (Notes and excerpts via Shamile Manie and Adli Yacubi’s transcription.)

TRC Testimony:

Hattas, Riefaat. Testimony at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Children’s Hearing, Athlone, Cape Town, 22 May 1997.

(As quoted in: SAPA, “TRC hears emotional testimony at children’s hearing,” 22 May 1997.)

Activist Testimony & Reparations:

“Govt ‘spits in face of apartheid victims’.” Mail & Guardian, 5 October 2000.

(Quoting Riefaat Hattas on the cost of struggle and reparations.)

Facebook Tributes & Community Memory:

Jason Patrick Hanslo, “#masekin: Riefaat Hattas,” Facebook, 5 May 2022.

Personal Correspondence and Memories:

Shamile Manie, WhatsApp messages to Adli Yacubi, July 2025.

Salih Davids, “My Brother in Islam, Riefaat” (tribute poem), July 2025.

Ebrahim Rasool, Janazah Tribute, July 2025.

Photographs:

Yunus Mohamed, “Call of Islam, Manenberg, 1980s.”

Published Blog Draft:

Adli Yacubi, “The Boy Who Waved Back: Remembering Riefaat Hattas of Manenberg,” unpublished manuscript and blog, July 2025.